Brian Long Consultancy & Training Services

Ltd.

August 2014

There is an update to this article for Delphi XE6 available here.

Accompanying source files available for

Delphi XE5, Delphi XE6,

Delphi XE7,

Delphi XE8 and Delphi 10 Seattle

are available.

Delphi Android apps can use Android APIs, both those already present in the RTL and others we can translate manually, in order to interact with parts of the Android system. This article will look at how we can make use of the NFC (Near Field Communications) API to access NFC tags in the same way as other Android NFC apps.

Through this article you should gain an insight into the techniques involved in building NFC apps and working with native Android NFC APIs, some of which are reasonably straightforward to employ and some of which involve metaphoricaly rolling up ones sleeves and getting ones hands dirty.

NFC tags have tag IDs so your app could just recognise an NFC tag and respond to it. However NFC tags can also have varying amounts of data written to them. This can include URLs, text or any other data. Your app can read this data and do things based upon what it finds.

An app that supports NFC tags can operate, broadly speaking, in one of two ways:

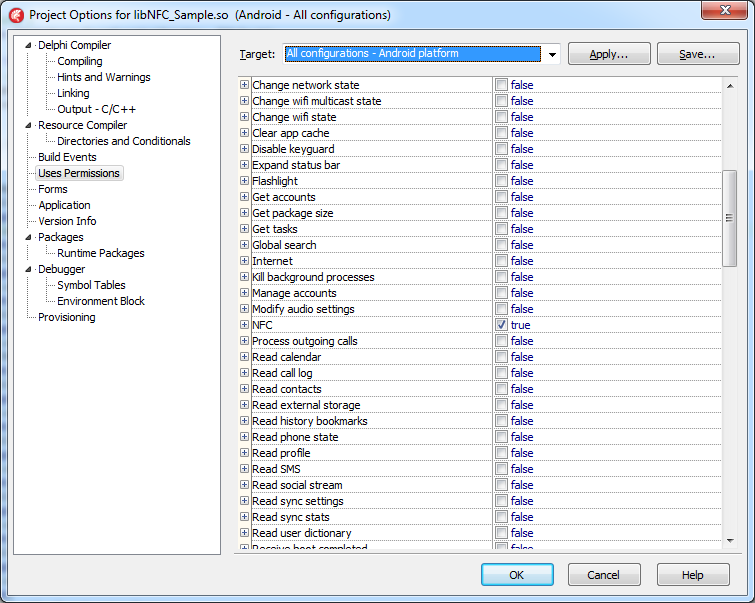

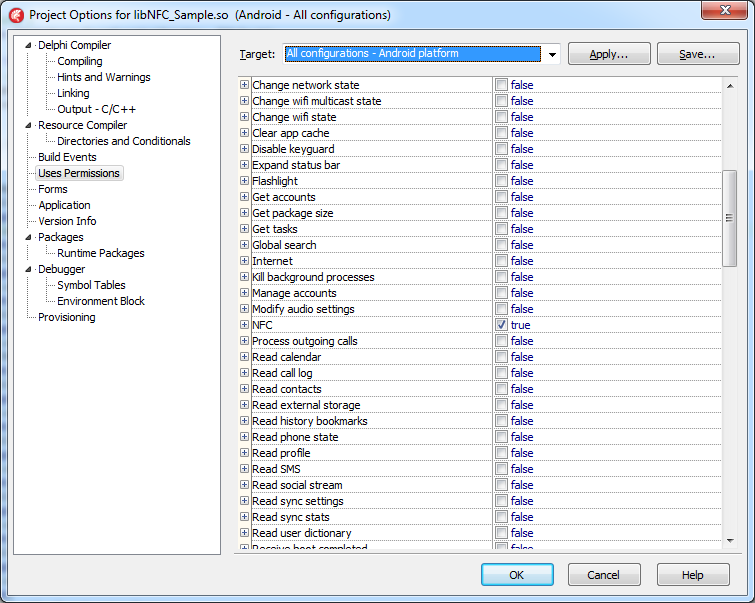

Either way the application setup will involve requiring permission to use the NFC sensor. In the project options dialog this is done in the Uses Permissions section:

If the use of NFC is crucial to the operation of your application you can also ensure this is known to the Android ecosystem. Indeed if you do this the Google Play online store will not list your app to devices that do not have NFC hardware. You do this by tweaking your Android manifest file, which as Delphi developers you cause to occur by editing the file AndroidManifest.template.xml that appears in the project directory when you first compile your mobile project.

Within the <manifest> element you add this child element, which

will be a sibling to the <application> element:

Before embarking on any NFC coding we need to have access to the Android NFC API. This is not provided as part of Delphi but that is not an insurmountable obstacle as there are various Android API import tools available. These import tools produce import units that follow the model used by those provided in Delphi's RTL. Delphi's native ARMv7 code communicates with the Java world using the Java Bridge (or JNI Bridge or Native Bridge as it is sometimes called) so these import units are often called Java Bridge units.

The ins and outs of using the Java Bridge interface to represent Java classes using

Delphi interfaces (one for the class methods and one for the interface methods,

bound together by the TJavaGenericImport-based generic bridge class)

are a bit beyond the scope of this particular article, but I did go into it in

my CodeRage 8 session on using Android APIs from Delphi XE5:

One such Java API import tool, Java2Pas, was discussed on FMXExpress. It has been used by the person behind FMXExpress to import all APIs in the Android SDK. The results, for a whole range of Android SDK versions, can be found in a Github repository, which is a very useful (even if not particularly usable) resource.

As hinted by the parenthesised comment it turns out the NFC import units (and maybe others - I haven't yet had the need to check) need work to be suitable as input to the compiler. Indeed if you pull down, say the API level 19 import units, android.nfc.*.pas from https://github.com/FMXExpress/android-object-pascal-wrapper/tree/master/android-19 you'll find they won't compile for a whole heap of reasons including a gamut of circular unit references.

Anyway, not being one to be thwarted I took the interfaces and put them into units that were more in keeping with what the compiler was expecting, fixed some errors in the definitions and the resultant import units are included in the example downloads. I've coallesced what I needed from the 27 import units into two units called Androidapi.JNI.Nfc.pas and Androidapi.JNI.Nfc.Tech.pas.

Bear in mind that documentation for the various classes represented by these Java Bridge interface definitions can be found here and here. Additionally the Android documentation contains general NFC programming advice (targeted at Java programmers, but still useful background nevertheless), which can be found here.

Building an application that hooks into the NFC tag dispatch system is reasonably straightforward when you have the required API imports and have read the Android documentation on the matter.

In the downloadable source archive that accompanies this article there is an example app that uses the NFC tag dispatch system in the 1_TagDispatch subdirectory.

To tell Android to launch your application you must add additional intent filter definitions into the Android manifest for your application's main activity (the Android UI object that Delphi forms are rendered within). These are statements from your application saying that when a particular NFC action needs to be handled your activity can do the job. An intent is an Android system message represented as an object with varying amounts of associated data available through various methods.

When Android scans an NFC tag it parses the data on it to see if that data is of a known type, such as a URI or plain text. Then Android will locate a suitable activity to launch to handle the NFC tag. If more than one activity has registered an interest in the same tag capabilities then an activity chooser dialog is presented to the user.

In the case of an NFC tag containing NDEF (NFC Data Exchange

Format) records Android will parse the data and work out the MIME type

or URI. It will then launch an activity that has registered an intent filter for

ACTION_NDEF_DISCOVERED

(see Android documentation here) with the appropriate MIME type

or URI scheme as additional criteria.

If no activity registered an intent filter for the MIME or URI specifics on the

tag, or if the tag contains NDEF data not of a MIME/URI type, or if the NFC tag

is of a known tag technology but does not contain NDEF data then Android will launch

an activity registered for the

ACTION_TECH_DISCOVERED intent (see Android documentation here).

Finally, if no activity handles either the ACTION_NDEF_DISCOVERED or

ACTION_TECH_DISCOVERED intents then Android looks for one that will

handle the ACTION_TAG_DISCOVERED

intent (see Android documentation here).

Having seen the general description let's now see some specifics of what we'd need to add into AndroidManifest.template.xml to register for some of these intents.

Any intent filter we add needs to be added as a child element of the existing

<activity> element and as a sibling of the existing intent filter

for the LAUNCHER category of the MAIN action (this existing intent filter is how

Android knows which activity to list for an application in the apps list).

Let's say you want your application to specifically respond to an NFC tag that has

an NDEF record containing the URL of my web site:

http://blong.com. This can be done by crafting an intent filter or two for

ACTION_NDEF_DISCOVERED, for example:

So here we are looking for any NDEF recognised data format where it is a http URI with either of the two host names that represent the site. If Android scans an NFC tag with either of those URLs then the app will be launched.

Similarly if you want your application to respond to an NFC tag containing plain text you define an intent filter specifying the plain text MIME type thus:

If you want your app to launch if either the specified URL or plain text is found on a scanned tag then you simply include both intent filters, and correspondingly you can add in any additional ones that make sense for your application as required.

If you want the URL response to be more general, so have the app launch for any URL, you would modify the intent filter like this:

You can use your imagination and try other combinations.

If you aren't particularly interested in any specific data or data type you can

instead look at the second of the two intents: ACTION_TECH_DISCOVERED. There are a variety of independently

developed NFC tag technologies that may be present on a given tag and these are

all represented by Android classes as listed on this documentation page. This intent focuses on responding

to specified subsets of these technologies, which you list in an XML resource file

that you need to add to the deployment profile for your mobile FireMonkey project.

Each technology subset you want to respond to is set up in a <tech-list>

element in the resource file. You can see examples of how the resource file might

look on this Android documentation page. For example if you want

to respond to tags that support MifareUltralight, NfcA and Ndef technologies you

would need an XML file that looks like this:

Alternatively if you want your app to respond to any technology at all you could

set the resource file up with each technology specified alone in its own <tech-list>:

To set up this resource file for a Delphi Android app you first save it as an XML

file. I recommend creating a res directory in your project directory

and creating an xml subdirectory within that. So for example your resource

file could be called res\xml\nfc_tech_discovered_filter.xml, relative

to the project directory.

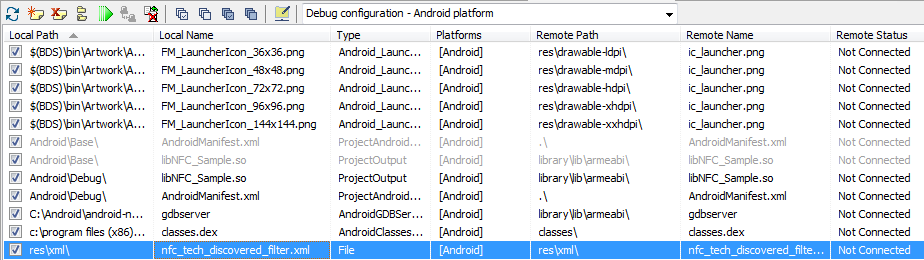

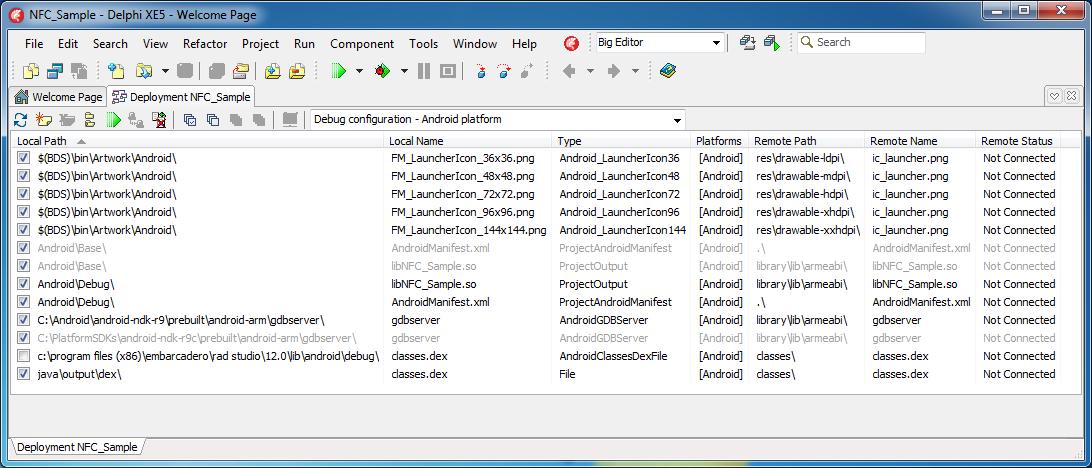

Once the file exists you can add it to the Delphi project deployment manager. In Delphi choose Project, Deployment to invoke the deployment manager. Hit the deployment manager toolbutton whose tooltip says: Add Files. Navigate to find your XML file and press Open to add your file to the deployed files list. Set up the deployment of this file by changing these column values in the deployment manager for your resource file:

res\xml\This should leave the deployment manager ready to deploy your file:

With the resource file set up you can now add the required intent filter into the

Android manifest template file that refers to it via a <meta-data>

element:

The @xml reference in the resource string tells Android to locate the

resource file in the xml directory of the standard Android res

directory that Android apps typically include, compressed inside the final .apk

Android package file.

If no application has responded to the scanned NFC tag through ACTION_NDEF_DISCOVERED

or ACTION_TECH_DISCOVERED then the final option of ACTION_TAG_DISCOVERED

comes into play. You can register an interest in this intent by changing the Android

manifest template thus:

Now we have the infrastructure nailed down we can look at what goes into the application to make it work when it gets automatically launched by Android when a suitable NFC tag is scanned.

The key to getting the app to work is to run some code when the application starts

up and becomes active, so the form's OnActivate event would be helpful

here.

In the OnActivate event handler we must

get the intent object that was passed to our activity by Android as that contains

a "parcelled" copy of the tag object for us to examine and make use of:

That takes us to a crucial point of being able to get to work on the tag object.

We'll come back to how to get the tag object out of the intent object and then pull stuff from an NFC tag object later.

I should be honest here and say that the tag dispatch system sample does demonstrate

a shortcoming here. If you have the app launched by Android for a tag then all is

well. However if another NFC tag is scanned while the app is in the foreground then

the app will crash, citing an error relating to there no being a looper for the

current thread. I haven't yet followed this up to see if there is a convenient

way of mitigating the problem. I did eventually resolve this when

working against later versions of Delphi. The Android manifest has an optional

launchMode attribute

for the activity, which needs to be set to singleTask. If you hit this problem you'll need to add in that

attribute.

The NFC foreground dispatch system is often the more interesting aspect of NFC tag reading as this is where an application "owns" the NFC sensor and can read whatever tags are presented to the device. However it is also the more cumbersome to implement as it requires some Java work to implement what the documentation tells you is required.

In the downloadable source archive that accompanies this article there is an app that uses the NFC foreground dispatch system in the 2_ForegroundDispatch subdirectory. We'll look at what is involved in building such an application in this section.

The basics as far as Android itself is concerned are as follows. To take control

of the NFC sensor and enable the foreground dispatch system you call the default

NFC adapter object's enableForegroundDispatch() method. To disable it

you call the corresponding disableForegroundDispatch() method.

An application will be expected to enable the foreground dispatch system when it

comes to the foreground and disable it when it leaves the foreground. If you use

the IFMXApplicationEventService FMX platform service to set up an application event handler,

this corresponds to when the event handler is triggered with the aeEnteredBackground

and aeBecameActive values from the TApplicationEvent enumerated type values.

When the foreground dispatch system is active Android will scan NFC tags and send

a suitable intent direct to your running activity by calling its onNewIntent() method. The intent will contained a

"parcelled" copy of the tag object.

So that's how Android sees things - quite straightforward really. Unfortunately when it comes to porting this over to Delphi things quickly get rather messy.... :-/

However before we get onto the tricky parts (calling the NFC foreground dispatch system methods and receiving new intent objects) let's get some housekeeping sorted out. When the app starts it needs to be able to call NFC APIs and rather relies upon NFC being enabled, so let's check if that's the case. If it is not we can launch the system settings page for NFC to help the user out.

To get access to the NFC adapter we call the getDefaultAdapter() class method of the NfcAdapter class, passing in our activity context.

The adapter's isEnabled() method tells us if NFC is switched on.

If not we construct an intent object passing in the activity action that shows the

settings and pass that intent to our activity's startActivity() method (see here for more on this method) and leave the rest

to the Android system and the user. Additionally a toast message is displayed, making

use of my toast import unit, discussed elsewhere.

The Androidapi.JNI.GraphicsContentViewText.pas unit in the uses clause

is part of the Delphi RTL and gives us access to JIntent, the Java

Bridge representation of Android's Intent class. Androidapi.JNI.Nfc.pas is one the new pair

of units crafted to make use of NFC (as mentioned earlier).

Androidapi.JNI.Toast.pas is my import unit I made to import the Android toast message

functionality.

FireMonkey provides much functionality necessary for business applications needing to access data and display it to the user, but some common aspects of the Android OS are not 'wrapped up' in FireMonkey classes.

At this point you can call upon the various Android APIs that have been provided in the RTL, or craft or import new Java Bridge APIs if need be (as per the NFC API discussed earlier).

In cases where this isn't simply a case of calling into more APIs whose declarations need to declared with Java Bridge interfaces this poses a problem. Some examples of areas of the Android OS that are not wrapped up in XE5 and are difficult to incorporate include:

In Delphi XE5 these things and more require additional Java code to implement. Then some light hacking is needed to make use of this Java code in a Delphi application, which tends to get in the IDE's way, so IDE building/installing of the application becomes interesting, and debugging becomes next to impossible. These consequences tend to force you into managing a pair of synchronised projects:

Over and above this general Android integration isue there is also a problem with the level of support of Java APIs offered by Delphi's Java Bridge functionality. It turns out that Java Bridge can handle a good chunk of the Android API, but in the case of a method that takes a 2D array we become unstuck. Support exists for normal parameters and 1D arrays currently.

The NfcAdapter.enableForegroundDispatch() method has

a signature containing 4 arguments:

PendingIntent object that describes the intent to use

when an NFC tag is scannednull/nil to respond to all scanned NFC tags (for

ACTION_NDEF_DISCOVERED and ACTION_NDEF_DISCOVERED, coded

versions of what we saw earlier)null/nil

for any NFC tag technology (for ACTION_TECH_DISCOVERED, programatic

equivalent of the XML resource file we saw earlier)

Notice that 4th parameter? It's a 2D array. This means that the Java Bridge is incapable

of representing this API currently. So this means we are obliged to make the calls

to it (and for symmetry, to its companion API disableForegroundDispatch()) from Java code.

Given the expectations of how the methods should be called it would be wise to inherit

from the FireMonkey activity class and override the standard Android lifetime methods

onResume() and onPause() and call the NFC foreground dispatch

control methods from there.

We'll get on to setting up the descendant activity presently, but for now let's assume it's been done so you can see what the Java code that we'll add into the class to toggle the NFC foreground dispatch system looks like:

Here we see some standard activity methods being overidden to set things up and do

what is required: onCreate(), onResume() and onPause().

To receive the intent that Android will send when the foreground dispatch system

scans an NFC tag we need an onNewIntent() method. However the Android activity

present in our FireMonkey Android application doesn't offer us a convenient onNewIntent()

override. Just as above, this means we will need to inherit from the default activity

we get in our application.

The specifics of the approach to inherit a new (Java) activity class and have it call some Delphi code from an overridden method requires some of the aforementioned light hacking. This may seem rather onerous and cumbersome but it is what it is and, in Delphi XE5, it is necessary.

The steps required for responding to a new intent are as follows:

onNewIntent() method that calls into a

native method, which we'll implement in Delphidx.batDexMerger classThat's quite a daunting list but fear not. Fortunately many of the Java-oriented steps can be wrapped up by a suitably crafted batch (.bat) file or command script (.cmd) file. And I'm sure if you really wanted to, you could also create a PowerShell script to do the same, but I've stuck with the old scripting that I know how to work with.

The standard activity in any Delphi application is a Java class called FMXNativeActivity

in the com.embarcadero.firemonkey package (or namespace), which actually

inherits from the Android NativeActivity class. We need to inherit from FMXNativeActivity,

override onNewIntent() and have it call a native method with an equivalent

signature. Here's the code I rustled up for the job, which can be found in the

java\src\com\blong\nfc directory under the project directory in a file

called NativeActivitySubclass.java.

Note that the actual Java source code also includes the pause/resume code that toggles the NFC foreground dispatch system that we saw earlier.

You might notice the Java code presented thus far has a bunch of trace statements

in (calls to Log.d()). You can also emit the same type of trace

calls from your Delphi code by ensuring FMX.Types is in your uses clause and calling

Log.d there. These trace statements can be viewed in the

Android Device Monitor or its deprecated predecessor Dalvik Debug Monitor Server (DDMS).

In the java project subdirectory is a batch file called build.bat.

Before invoking the batch file you must ensure you have done the required preparatory

work.

Prep step #1: The first preparatory job is to add a few directories from the Android SDK and the JDK to your System path.

You can do this either:

PATH environment variable using steps outlined here or here

SET commandsSET commands

Note that the required directories will vary depending on whether you already had

an Android SDK installed, or whether you let Delphi install the Android SDK and,

if so, where you told it to install it. For example you may have already installed

the Android SDK in C:\Android\android-sdk-windows, or Delphi may have

installed it into C:\Users\Public\Documents\RAD Studio\12.0\PlatformSDKs\adt-bundle-windows-x86-20130522\sdk\android-4.2.2

or you may have given Delphi a specific target directory, meaning the Android SDK

path is, say, C:\PlatformSDKs\adt-bundle-windows-x86-20130522\sdk\android-4.2.2.

Directories to add to the path are:

build-tools directory,

which might be C:\Android\android-sdk-windows\build-tools\18.0.1 or

C:\Users\Public\Documents\RAD Studio\12.0\PlatformSDKs\adt-bundle-windows-x86-20130522\sdk\android-4.2.2

or somewhere else altogether.bin directory, which will be something along the lines of

C:\Program Files (x86)\Java\jdk1.6.0_23\bin or C:\Program Files\Java\jdk1.7.0_25\bin.

I'd certainly recommend extending the Windows search path permanently through the

environment variables option in the system properties dialog so you can run Android

SDK commands and Java commands at any point going forwards, but if you wanted to

run SET commands at the command prompt or from within the batch file

they might look a little like this:

Once the system path has been updated you will be able to successfully launch the following executables from a command prompt. If you updated the global path then it will be any command prompt launched after you've made the change. If you changed a local environment by running commands at a command prompt then you can run the commands from that command prompt. The commands are:

If you cannot launch any of these commands then go back and review your path settings as they are likely wrong.

Prep step #2: The next preparatory job is to open the batch file in an editor and make appropriate edits to ensure the various environment variables set at the start are correct.

This is what the batch file looks like:

You should modify the set commands for the following environment variables

and ensure they refer to appropriate existing directories:

ANDROID - this should point at the Android SDK installation directory,

e.g. C:\Android\android-sdk-windows or C:\Users\Public\Documents\RAD

Studio\12.0\PlatformSDKs\adt-bundle-windows-x86-20130522\sdkANDROID_PLATFORM - this needs to be set to one of the installed Android

SDK platform directories, found in the Android SDK's platform directory.

The Delphi installed SDK installs the android-17 platform directory.DX_LIB - This needs to be set to the directory containing the

dx.jar Dalvik support library. This is found in the lib directory

2 levels under the Android SDK's build-tools directory. You will need

to look to find the correct intermediate directory for your SDK installation. The

batch file suggests this may either be something like android-4.2.2

or something like 18.0.1.EMBO_DEX - should point at a classes.dex file shipped

with Delphi. My installation has one stored as C:\Program Files (x86)\Embarcadero\RAD

Studio\12.0\lib\android\debug\classes.dex but the environment variable

value is surrounded in quotes due to the spaces in the path.Prep step #3: The final preparatory job before running the batch file is to generate a compiled Java version of Embarcadero's classes.dex file, which will be a file called classes.jar.

The current classes.dex file, found in C:\Program Files (x86)\Embarcadero\RAD

Studio\12.0\lib\android\debug and also in C:\Program Files (x86)\Embarcadero\RAD

Studio\12.0\lib\android\release was compiled Java code, but has been

run through the Android SDK dx tool to generate DEX (Dalvik Executable)

code. We need to undo that step to give us a file we can use to help our descendant

activity class compile ok.

To turn a .dex file back into a .jar file you can use the open source Dex2Jar tool. Once you've installed Dex2Jar you can use a command like this to process the file:

d2j-dex2jar.bat -o classes.jar "C:\Program Files (x86)\Embarcadero\RAD Studio\12.0\lib\android\debug\classes.dex"

Be sure to put the new classes.jar file in your project's java subdirectory.

Beware that if you move to a different version of Delphi, which includes applying update packs to your current version of Delphi, then you will need to re-do this in case the code in classes.dex was updated and/or changed.

Prep steps are now complete

Now, at long last, we can run the Java build script...

To run the build script requires you to first launch a RAD Studio Command Prompt - you can do this in Windows 7 or Windows 8.x by going to the Start menu or Start screen and typing:

RAD Studio

and then selecting the RAD Studio Command Prompt item that is found. Or you can just hunt through the program groups to find it.

In the RAD Studio Command Prompt you should change directory to the one containing

the build.bat batch file and then invoke it by running: build

This should proceed to:

dx.bat Android SDK scriptDexMerger class in the dx.jar libraryIf any of these steps fails then you should review the environment variables and see which one has not been set correctly.

After a successful build you will have a new classes.dex file in the

project's java\output\dex directory, which contains the native activity

descendant class that will respond to launched activity results in addition to all

the regular FMX Java code and Android support library included there by default.

At last it is time to open the sample project in the Delphi XE5 IDE. The main UI-based functionality in the application is quite trivial. Before looking at the code, however, we have a little more setup to do in the IDE, so choose the Project, Deployment menu item, which gives us this:

You should note that the normal classes.dex file from the RAD Studio

directory has been de-selected. Instead, the newly created classes.dex

in the java\output\dex directory has been selected to be deployed to

the same place: the Android package's classes directory. This gets

our native activity descendant class on board within the Android package file.

You should be aware that the Deployment Manager in Delphi XE5 has a problem with

substituting alternate versions of classes.dex into Android application

packages. The problem is logged in Quality Central as QC 118472.

The issue manifests itself by Delphi automatically re-selecting the default shipped

classes.dex when you switch configurations in the Deployment Manager.

This overrides the replacement version and so things very much stop going according

to plan, so keep an eye open for this issue occurring.

The Java code calls down to a native onNewIntent method, which is implemented

and registered in the code you see below. As you glance up and down the code you

might observe that it's a bit hairy, but let's look through it and see if we can

get a handle on it.

The actual native Delphi routine is in fact implemented as the OnNewIntentNative

function. Like all JNI functions it uses the C calling convention and has the same

first couple of arguments. The first argument is the JNI interface pointer,

through which we manipulate Java objects. The second argument points to the Java

object for an instance method or to the Java class for a class method, rather like

Self does in Delphi methods.

After these initial arguments we have JNI representations of the argument taken

by the Java onNewIntent() method, which in this case is a reference type - an Intent object reference.

The intent argument becomes a JNIObject, which is Delphi's version

of the JNI specification's jobject type, used to represent reference

types.

When this native method gets called we queue up some code to run in the FMX thread (remember that

the JNI native routine is invoked in the Java UI thread). The code invokes a method

on the main form passing the received parameters, wrapping the JNI intent parameter

in a JIntent Java bridge (aka JNI bridge or Native Bridge) interface

reference to give the form method access to the Java intent object. The called method

has been added to look like a regular method, maybe even look a bit like an event

handler, to handle the new intent that is passed in.

Ahead of any callbacks actually occurring this JNI routine must first be registered

as the implementation of the native method onNewIntent(), which can

be called from Java. This task is performed by RegisterDelphiNativeMethods,

which gets called in the form's OnCreate event handler.

RegisterDelphiNativeMethods uses an RTL helper to get a JNI interface

pointer (the same sort of thing that is given to a JNI method as the first parameter)

that will allow the FireMonkey activity object to be manipulated. Then it fills

up a JNINativeMethod record with information that JNI can use to map

the Java method name and signature to our Delphi routine. Getting the right signature

in the relevant format requires a little bit of know-how.

The trick here is to use one of the JDK tools to dump information about NativeActivitySubclass

and this will give us the appropriately encoded signature information. The tool

in question is javap.exe: the Java class file disassembler.

As it is currently set up the build script deletes all the intermediate files, including the compiled activity descendant. So to work this step through (if you really want to run it - bear in mind I've already done this and used the information gleaned therein within the code) you'd need to re-run the build script after commenting out (or deleting) the tidying up section, particularly removing this line:

Now inside of your project's java\output\classes\com\blong\nfc directory

you will have a few .class files. From your project's java directory

you can run this command:

javap -s -classpath output\classes com.blong.nfc.NativeActivitySubclass

and this will emit information about all the method signatures of the specified class. I've highlighted the key pieces of information that have been used to set up the JNI registration record.

RegisterDelphiNativeMethods then proceeds to use JNI routines to get a local reference to the FireMonkey activity object's class,

which it uses to register the native method against (the native method is

part of our app's activity class) before cleaning up the local reference.

There is quite a bit to think about when setting this up in a new application but hopefully with the various steps explained it at least becomes understandable.

After that tortuous journey we can now actually write a handler for the new intent in order to work with the scanned NFC tag!

This is now essentially the same position that we were in earlier with the tag dispatch system. We need to extract the tag and process it, which we'll look at shortly. Let's first finish the run through of the tricky side of this kind of Android programming with Delphi XE5.

The application can now be compiled to a native Android library and then deployed into an Android application package (.apk file) using the Project, Compile NFC_Sample and Project, Deploy libNFC_Sample.so menu items respectively.

If you wish you can skip those two steps and have them done implicitly by choosing

the Run, Run Without Debugging menu item (or by pressing Ctrl+Shift+F9).

This will uninstall the app if already installed, and then install the new version

onto the target device.

Note that despite choosing the Run Without Debugging menu item, the application

will not be launched on the target device. The same is true if you choose Run, Run

(F9). This is due to another shortcoming of the IDE in which it assumes

the launch activity will be the stock FireMonkey activity and so is unable to contend

with the situation we have here where we are using a descendant of the stock activity,

which has a different class name. This issue is open in Quality Central as QC 118450.

Clearly with the issues with launching the application there is no possibility of debugging your code. You cannot attach to a running Android process as you can with a Windows process, for example.

If you need to actively debug (as opposed to some agricultural equivalent such as

using calls to Log.d from the FMX.Types unit) then it is incumbent upon you to set

up a pair of almost-mirror projects. One project will have all these hacks described

thus far on this page, and will enable launched activity results to be received

by your app. The other project will use the same application logic and units, but

will ignore all aspects of setting up activity result response. Consequently this

second project should support regular Android app debugging.

After all the preamble of how to set up the code for the two approaches to coding up an NFC app using either the tag dispatch system or the foreground dispatch system we can now look at the NFC tag object itself.

Both approaches ultimately end up with a tag object parcelled into an intent object that is delivered into your code. We need to pull out the tag object and inspect it and see what we can glean from it.

Here is the code from the second sample app's OnNewIntent method. The

first job is to ensure that the intent really represents a scanned NFC tag by checking

it against the 3 possible intent actions discussed above.

This foreground dispatch sample app starts with a prompt label suggesting the user scans a tag. If we now have an intent containing a scanned NFC tag object then the prompt label is cleared.

Now we get the tag from the intent as a Parcelable object (Parcelable is an

interface implemented by all parcelable objects, including NFC Tag objects).

In Java we would simply cast the object back to a Tag but it's a trickier

exercise in Delphi. To do the cast operation we must get a reference to the ILocalObject

interface implemented by all Java Bridge objects. Through this we get the underlying

object ID - an opaque pointer to the Java object. This object ID can then be wrapped

up by the target Java Bridge class.

So now we have an NFC Tag object!

The code clears an information label in preparation for some text to be written

there and then calls a helper routine, HandleNfcTag, to get a dump

of what's in the tag object. HandleNfcTag takes as arguments the tag

object and also a reference to a routine that will be passed various data pulled

from the tag object - in this case I'm passing in an anonymous method that adds in the new text onto the information

label. When the function is done it will return a string containing the NFC tag's

ID bytes turned into text, which are written onto another label.

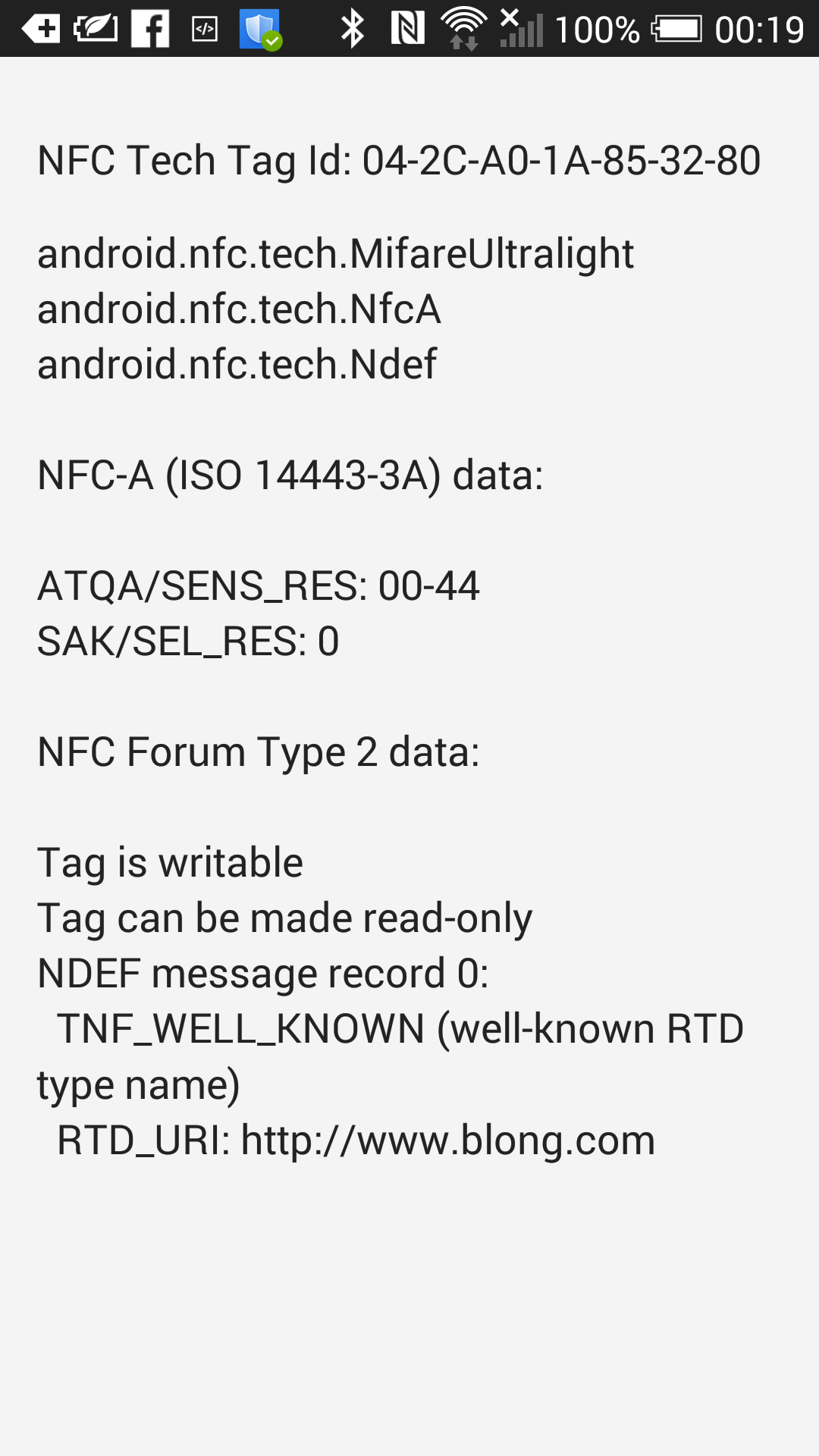

Before we delve into the guts of the helper routine, here's the simple sample app showing information read from a scanned NFC tag:

The top line of text is the text rendering of the NFC tag ID bytes. The rest is

information pulled from the tag object. In this case the technologies supported

by my tag are MifareUltralight, NfcA and Ndef, each of which are represented by

Android classes, MifareUltralight, NfcA and Ndef, which themselves are represented by

Java Bridge interface types in my Androidapi.JNI.Nfc.Tech.pas unit, JMifareUltralight,

JNfcA and JNdef. You can see an overview of the various

tag technology classes in the Android documentation here.

Here's the helper routine laid bare:

The first thing it does is pull out the tag's ID, which comes out as a Java array

of bytes. A helper routine in the unit (JavaBytesToString) iterates

over each byte calling IntToHex on it to build up the textual ID.

The next task is to list out the tag technologies. The tag's getTechList() method returns them as a Java array

of strings so a loop iterates across them adding Delphi string versions of them

into a TStringList.

There are a variety of tag technologies as listed here and here. Both pages divide them into mandatory technologies, supported on all Android devices, and optional ones. However one of the pages lists seven mandatory tech types and the other lists just six, so the story is a little unclear. I haven't followed it up yet (it wasn't too important to me) so am currently unsure which is correct.

The sample code just pays attention to six mandatory tag technologies and checks for each one in turn. If the tag technology is supported by the tag then the tag is passed along to one of six helper routines designed to dump information for each of these tag tech types.

Five of the six dump routines are simple enough. They make use of the various methods exposed by the Java tag tech objects and add the results to the information string:

It's the Ndef tag tech type dissection that contains all the

interesting bits. As the documentation page illustrates there are four types of standardised

NFC tags that support NDEF data. The methods in the class allow you to ascertain

certain standard information, such as the tag type (one of the four standardised

types), whether the tag is read-only or not, whether the tag can be made read-only,

the maximum NDEF message size and so on.

You can download the formal NDEF specification to get full details on the layout of data in an NDEF message from the NFC Forum or you can get summary information on the Android documentation site. For the sake of the sample we'll try and keep it simple.

On an NDEF tag is an NDEF message containing one or more NDEF records. We'll look through the records and see if they contain some information we can dump out.

You can get hold of an object that represents this NDEF message in the form of an

NdefMessage object. You can either read a cached NDEF message that was read when the tag

was discovered, or read the current message, on the off-chance it may have

been updated. The sample code reads the cached message.

An

NdefMessage object offers a getRecords() method that returns a Java array

of

NdefRecord objects. Unfortunately when iterating over the record

array and trying to access each record therein we hit upon some crash bug whereby

the record objects aren't surfaced correctly for us. Fortunately we can work around

this problem by pulling the raw object ID from the array wrapper and manually wrapping

it into a JNdefRecord Java Bridge object. Props to Daniel Magin for

spotting that issue and working out a nifty way round it!

As you can see the record object offers a getTnf() method to learn

its TNF or Type Name Format field. This is a 3 bit value with values available as

constants in the NdefRecord class (see here). The TNF value dictates how you should parse the data

in the rest of the record. In the case of TNF_WELL_KNOWN, which has a value of 1, the record

is one of a number of well known types and so the NFC Forum's Record Type Definitions

(RTD) kick in.

The RTD is a byte array and obtained through the record's getType() method. You match it to one of the RTD

byte array fields offered by the NdefRecord class to see which

known type it is, and thereby you can determine the NDEF message record payload

format.

The NFC Forum makes available the payload format for plain text, URI and smart poster.

The documentation there also confirms that the RTD byte arrays for text, URI and

smart poster are byte equivalents of T ($54), U ($55)

and Sp ($53, $70) respectively. The sample code caters for the first

two of these three but doesn't cover smart poster format.

I'll leave the code that decodes text and URI NDEF records out of this article and refer you to the sample code to see it instead. It would serve no specific benefit to the business of how to access NFC tags when it is really just a case of parsing byte arrays.

The key thing to take away from this article is that Delphi apps can make good use of NFC tags in either mode of standard NFC reading you choose.

Before leaving the subject we probably ought to also look at how to write to an NFC tag.

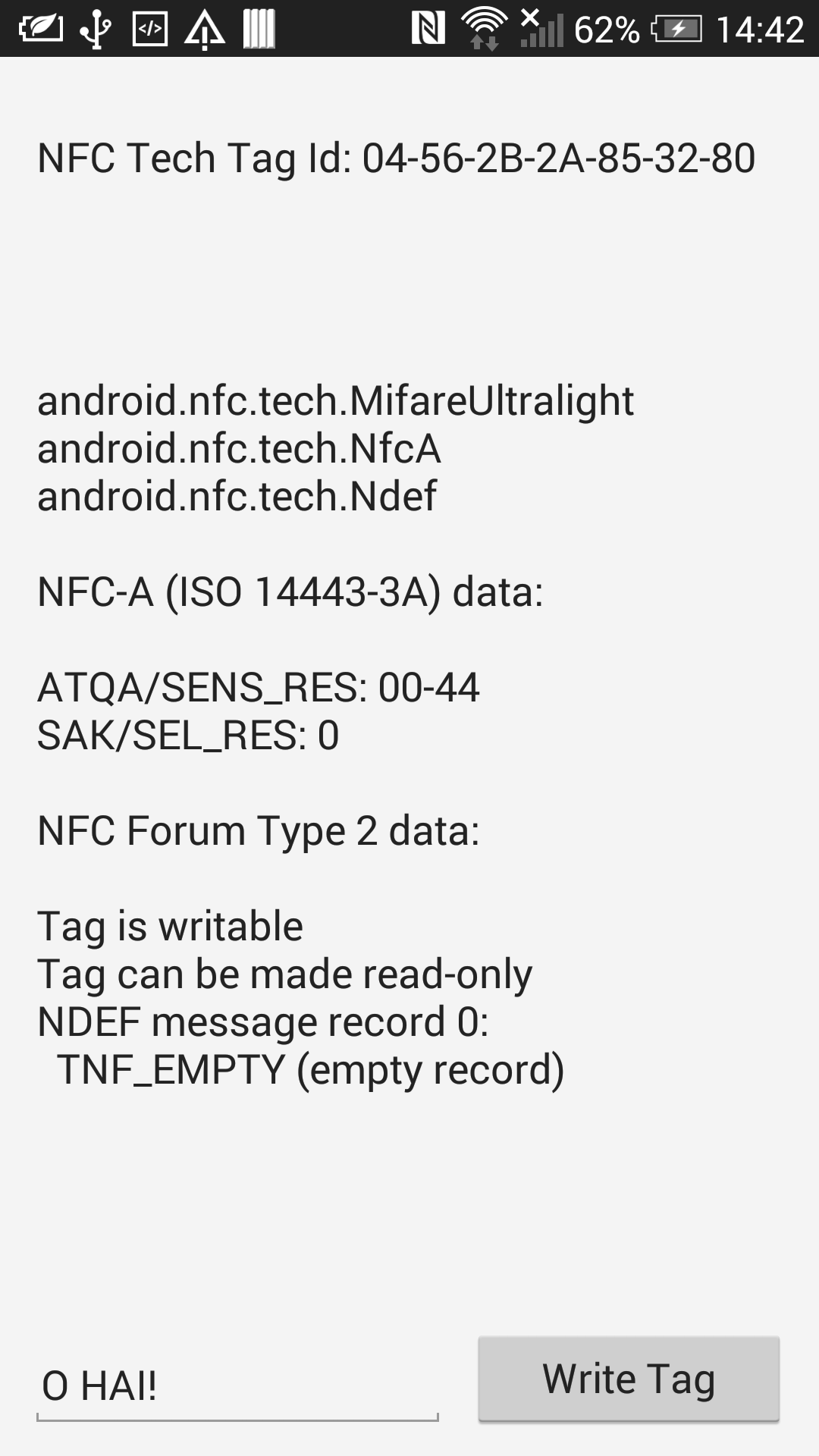

A common approach is to write an NDEF record to the tag, assuming the tag supports the NDEF technology. So the actual sample shipped in the downloads for this article really looks like this:

You can see text can be entered at the bottom of the form and the button can be used to write the text in an NDEF record in an NDEF message to an NDEF-compatible tag.

Incidentally, the sample app has an obvious shortcoming in that I haven't done anything to move the edit control up when the virtual keyboard appears on the screen, so when typing in text you can't see what you are typing into. However in this context that is an irrelevance.

The button has this code for an event handler:

It gets the activity's intent and pulls the NFC tag object from it. Note that in the earlier code we set the activity's intent to any new intent that we were delivered by the foreground dispatch system.

The tag then gets passed to a helper routine that looks like this:

This code tries to get an NDEF tag technology object for the scanned tag, which will only work if the tag is NDEF-compatible. Assuming we get the NDEF tag tech object we next open a connection to the tag in order to write to it, and also to later close the connection.

Assuming we establish a connection to the tag (which relies upon it still being

there) we can build up a message to write. The NdefMessage class has

a constructor that takes a Java array of NdefRecord

objects, so we set up a suitable array of records.

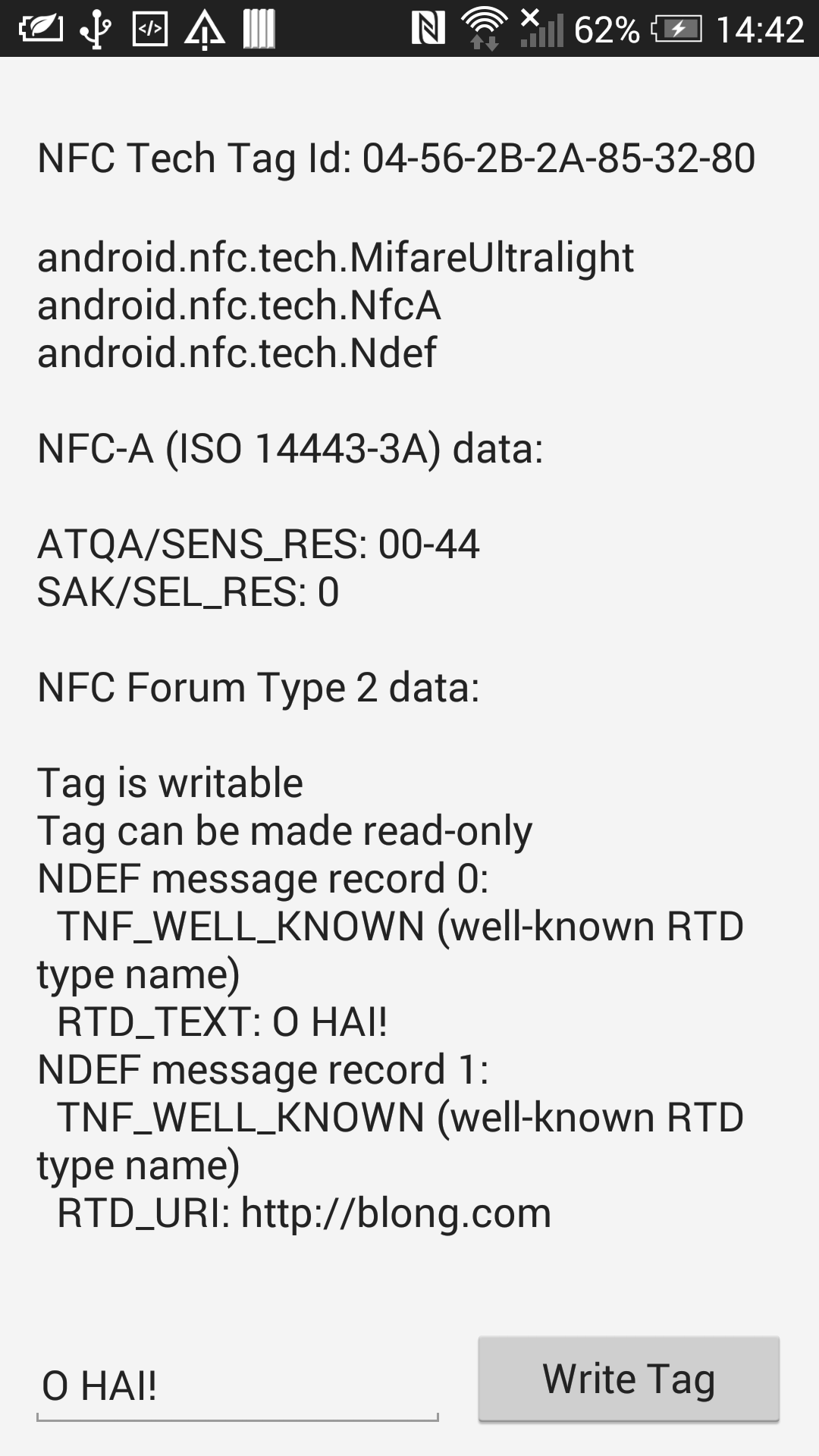

In this sample app's case we write out 2 records - one is the text record generated

by another helper routine, EncodeText, and one is a URI record generated

by a static method of the NdefRecord class specifically for packaging

up URIs in the correct way. So as well as the text entered by the user the NFC tag

also gets a record containing my web site address.

Again, the details of encoding some text into a record aren't too important, but are available to read in the code sample. It just follows the information available in the NFC Forum text record type definition.

You can extend the functionality of your application by taking advantage of available Android functionality, including support for scanning NFC tags on devices that have an appropriate NFC sensor.

Writing code in an app that is auto-launched by Android when an NFC tag is detected is quite straightforward once you have the API imports available.

However having a regular app set up support for priority NFC tag scanning using the NFC foreground dispatch system is not quite so straightforward. Well, in a sense it is as the hard work of working out how to do it has been done for you <g>, but it is still a bit of a drag to set up in an app. The onerous Java-based steps for dealing with the problem are not outlandish, but they are definitely tedious and cumbersome.

There are some wrinkles in how this all comes together, but Delphi XE5 was Embarcadero's first stab at Android development support, so hopefully some of these wrinkles will smooth out over time and things will continue to improve in future product updates and releases.

Go back to the top of this page