Click here to download the files associated with this article.

If you find this article useful then please consider making a donation. It will be appreciated however big or small it might be and will encourage Brian to continue researching and writing about interesting subjects in the future.

Actions and action lists were introduced into the VCL by Delphi 4 in June 1998 (in all flavours of the product) and were apparently considered so important that they were the first addition to the Standard page of the Component Palette since Delphi was released back in February 1995. Action managers were later added in Delphi 6 (May 2001).

In 2012 Delphi XE3, C++Builder XE3 and RAD Studio XE3 have added the first iteration of action support into the FireMonkey cross-platform framework. FireMonkey is often generally abbreviated to FMX, but the second FireMonkey release in the XE3 products seems also to be often referred to as FM2. It is FM2, specifically, that introduces actions to the cross-platform world. Initially FM2 supports actions and action lists but does not support action managers yet.

It would appear that at the time of writing, over 14 years after the

introduction of actions, these

potentially very useful components have been much under-used by the Delphi community.

Maybe this is just because people don't know much about them. Maybe the TActionList

component should have been placed at the beginning of the Standard page rather

than the end.

Anyway, for those who have never had the time or inclination to look into what actions do or how they work, this article will explore their purpose, usage and internal operation, making sure to take a look at action bands and action managers as introduced back in Delphi 6 (May 2001).

The article closes with a look at how to install new, reusable actions into the IDE. Where possible sample applications are provided twice, once using the VCL and once using FMX.

Often in applications, there are several UI mechanisms to trigger the same functionality

(or command). For example a button, a menu item and maybe a tool button on a tool

bar or a speedbutton on a speedbar. Normally you set up this type of arrangement

by sharing OnClick event handlers between the various objects. Of course

you must set up the captions and various other properties of each control individually

and this also applies when you need to disable all the controls that can invoke

the command.

An action is a non-visual component that represents a user-generated command. It allows you to set up all the UI properties related to that command in one central place, along with the code required to execute the command and also code that can control if the command is available to the user or not. Actions are managed either through action lists, which are also non-visual components, or through an action manager (also non-visual).

You connect actions to various trigger controls which can invoke the action. The UI properties and command functionality are both automatically propagated from the action to these controls. If any property of the action is modified at any point, these changes are also immediately propagated. So for example, if the action gets disabled at any point then all the related controls are disabled in turn. Code that controls whether the actions are available or not is automatically called during idle time, meaning that UI controls that can invoke the action are automatically enabled and disabled as appropriate.

The trigger controls that are designed to invoke the action's code are called action clients. The controls affected by the action are described as action targets or simply targets. Normally, when you create actions in the IDE you do not explicitly specify action targets (there is no place to do so). Instead, the action's code affects various action targets. We will see how action targets gain more significance later.

Let's try implementing a simple application a few times, firstly without actions

in the normal way, then using actions. Hopefully, you will see that actions simplify

the development of application functionality and the management of a smooth UI.

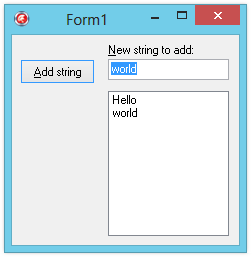

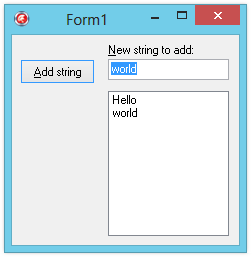

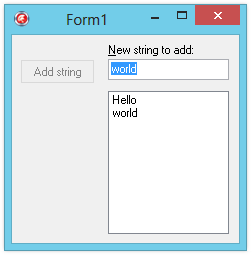

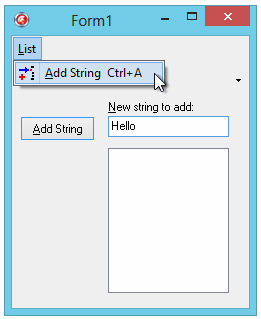

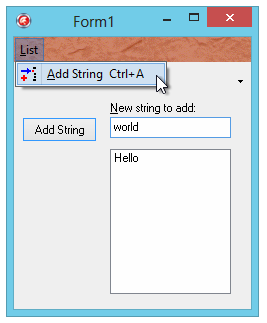

The application has an edit control (edtEntry), a button (btnAddString)

and a listbox (lstEntries), as shown in Figure 1. The button's job

is to add the edit's contents into the listbox. However, it only does this if the

edit control does not contain a blank string or a string already contained in the

list.

Figure 1: The application without actions

The first attempts will be without actions. There are two approaches we can choose

from. One is to implement the button's OnClick handler as shown in

Listing 1. As you can see, the basic job of adding the text into the listbox is

done here, as is the validation of whether to perform the job at all. In this case

the button is always enabled, but sometimes pressing it has no effect.

procedure TForm1.btnAddStringClick(Sender: TObject); begin if ( Length( Trim( edtEntry.Text ) ) > 0 ) and ( lstEntries.Items.IndexOf( Trim( edtEntry.Text ) ) = -1 ) then lstEntries.Items.Add( Trim( edtEntry.Text ) ); //Give focus back to edit edtEntry.SetFocus; //Highlight edit contents so it can be replaced by overtyping edtEntry.SelectAll end;

In more complex situations it could prove advantageous to split the actual implementation of the job from the validation code, as in Listing 2. Here, the validation is performed when the edit content is changed, and also after adding a string into the list. Invalid input in the list is avoided by ensuring the button is disabled when invalid data is in the edit, which perhaps gives a more intuitive user interface (see Figure 1). However to achieve this, the button must also be disabled in the Object Inspector, since the edit will start its life empty. This code can be found in the ActionLessApp.dpr project in the files that accompany this article (there is a VCL and an FMX version).

Listing 2: The functionality split from the validation

procedure TForm1.btnAddStringClick(Sender: TObject); begin lstEntries.Items.Add( Trim( edtEntry.Text ) ); //Give focus back to edit edtEntry.SetFocus; //Highlight edit contents so it can be replaced by over-typing edtEntry.SelectAll; //Trigger edit's OnChange to ensure button //is enabled or disabled as appropriate edtEntry.OnChange( edtEntry ) end; procedure TForm1.edtEntryChange(Sender: TObject); begin btnAddString.Enabled := ( Length( Trim( edtEntry.Text ) ) > 0 ) and ( lstEntries.Items.IndexOf( Trim( edtEntry.Text ) ) = -1 ) end;

Figure 2: Prototype number 2

As you can see, the validation is almost automatic, but not quite. When the text

is added to the list, the edit's OnChange event must be explicitly

invoked to ensure

that the button is disabled whilst the edit contains a string contained in the list

box.

Now think about what would be needed if more controls could invoke the string adding

behaviour. You would need to share the button's OnClick handler with

all the other controls. You would also need to set the Enabled property

of all the other controls in the edit's OnChange event handler. This

would quickly get messy to manage and maintain. This is where actions become very

useful, although they are just as appropriate when only a single control invokes

some behaviour.

In order to rebuild this application with actions and see how things change, let's get some basic background first. The full details will be covered later.

Actions are managed either by action lists (TActionList components

in Delphi 4 and later) or by action managers (TActionManager

components

in Delphi 6 and later). You can use as many action lists as you like, perhaps using

multiple instances to keep actions in different logical groups. Each action list

can be associated with a TImageList that contains small images that

can optionally be used to represent each action. If you have an image list set up,

use the action list's Images property to make the connection.

An action manager can act as a more functional action list, and can also link with existing action lists so that it can manage all actions in an application.

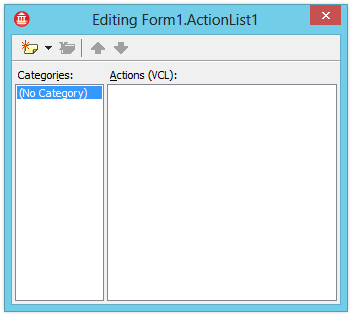

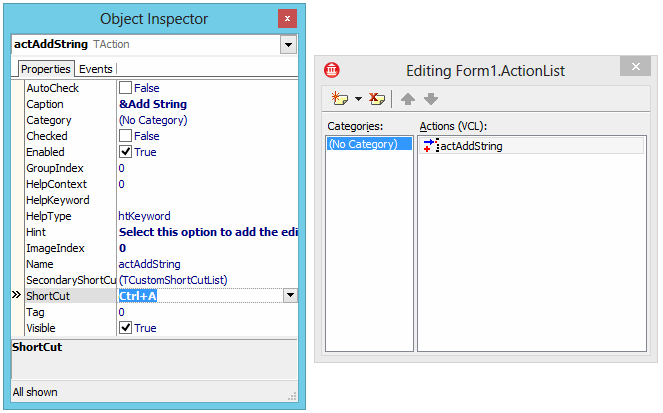

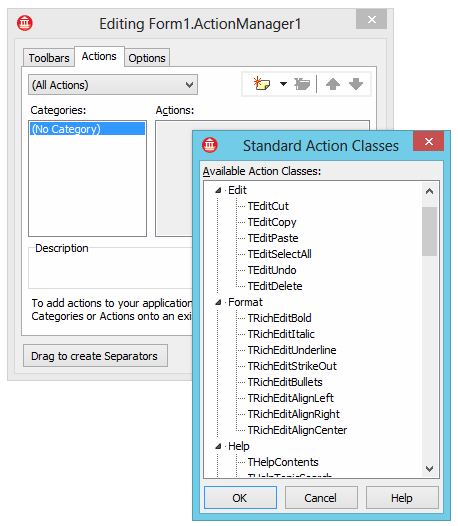

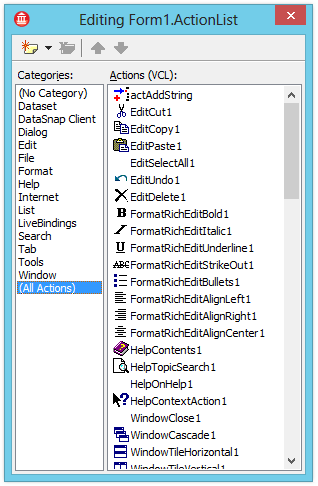

Once you place an action list on a form you can add actions using the Action List Editor available by right-clicking or double-clicking on it (see Figure 3). This allows you to create new actions and new standard actions (see later for details on standard actions).

Figure 3: The Action List Editor

Clicking the yellow button (or pressing Insert) makes a new action.

Whilst selected, the Object Inspector can be used to set up the UI properties that

represent the action. Figure 4 shows a new action with a number of properties including

a shortcut key (ShortCut) and an index into the action list's image

list (ImageIndex), although action images are not yet supported in

FMX. The action's image is shown in the

VCL action list editor.

Figure 4: Editing an action's properties

One property that warrants description is Category. All actions in

an action list can have a category (a string) but normal actions default to having

none

(a blank string).

You can choose categories for each of your actions and the action list editor will

list all categories in its left list box. When any given category is selected, only

the actions from that category are listed in the right list box. As your use of

actions increases, separating different actions into different action lists and

then having actions in a given list grouped by their categories, helps manage them.

The Object Inspector also allows you to set up a number of events for each action,

the most important of which are OnExecute and OnUpdate.

OnExecute should perform the job represented by the action. OnUpdate

should verify whether the action is still valid.

Suitable action event handlers for an action that can work in our application are shown in Listing 3 (they can be found in the VCL or FMX ActionApp.dpr project that accompanies this article). Notice that this time, unlike with Listing 2, the string adding code does not need to trigger the validation code. Instead it relies on the code being automatically called, which it will be (again, the details are coming).

Listing 3: Action event handlers

procedure TForm1.actAddStringExecute(Sender: TObject); begin lstEntries.Items.Add( Trim( edtEntry.Text ) ); //Give focus back to edit edtEntry.SetFocus; //Highlight edit's content so it can be replaced by over-typing edtEntry.SelectAll; end; procedure TForm1.actAddStringUpdate(Sender: TObject); begin (Sender as TAction).Enabled := ( Length( Trim( edtEntry.Text ) ) > 0 ) and ( lstEntries.Items.IndexOf( Trim( edtEntry.Text ) ) = -1 ) end;

At this stage we have not specified any action clients, although the code implicitly identifies action targets of the edit control and list box. However, these are hard-coded in source and so do not quite fit the normal definition of action targets (more on action targets later).

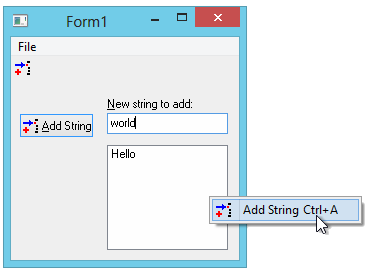

At this stage we need a way to invoke the action. Normal procedure would involve

adding action clients and connecting the action to them, but this is not

strictly necessary. The action has already defined a shortcut (Ctrl+A).

At run time, pressing Ctrl+A will automatically invoke the action if

it is available (in other words is enabled), which frankly, is rather clever.

In this application though, action clients are required. Drop a button on the form

and use the Action property to connect it to the only available action,

actAddString. It will immediately absorb all appropriate properties

and events from the action, which are Caption, Enabled,

HelpContext, Hint, Visible and OnExecute

(assigned to OnClick). These make the button look and behave sensibly.

When the button is clicked, the action will be invoked.

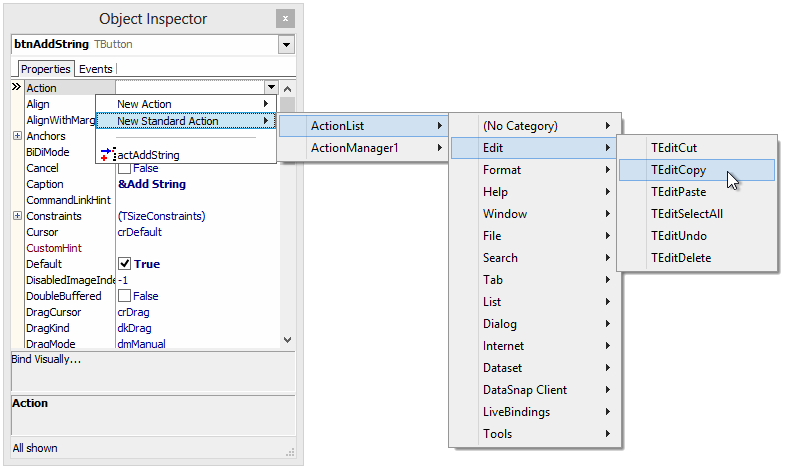

Note: You use the Action property to choose a

pre-defined action object to hook up to your action client control. However, if

an action list exists on the form you can also use one of the two additional

items added to the drop-down menu for the property editor in this

same Action property to either create a new action or choose a standard

action (see later).

Notice that the action's properties/events do not necessarily tie up with like-named

properties/events in the client (for example, the action's OnExecute

event handler

is assigned to the button's OnClick handler). This allows more flexibility

in associating

actions with a whole variety of action clients.

If the default action client invocation mechanism is not suitable (say for example

you want a control double-clicked to invoke the action, or the control has no

Action property) this is no problem. You can either make the control's

favoured event share the action's OnExecute event handler, if compatible,

or alternatively make an explicit call to the action's Execute method

in the control's event handler.

The action's OnUpdate event is regularly called during application

idle time (full details later) and so if any

of the validation conditions fail,

the action's Enabled property is set to False. This change

immediately propagates to the button causing it to become disabled, meaning that

when the action is disabled the action client cannot trigger the action. The program

running looks much like Figure 2 so another screenshot is pointless.

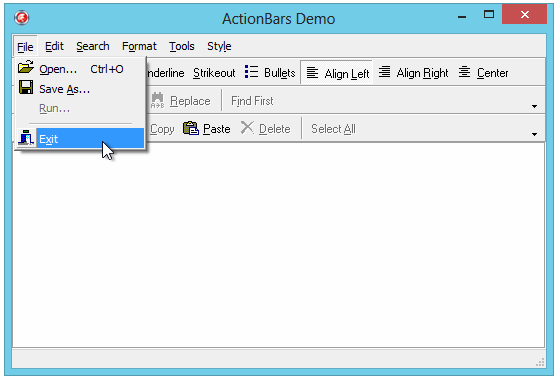

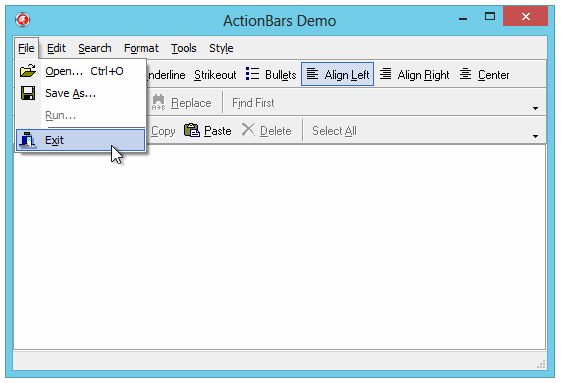

ActionApp2.dpr is another project, much like ActionApp.dpr

but with additional controls. In the VCL app a TBitBtn

is used instead of a TButton (which allows a small bitmap to be rendered

on its surface). Also, it employs a popup menu for the list box, a main menu and

a toolbar with a button on it. You will not be surprised to learn that each of these

controls is hooked up to the action to prove a point. The action's properties propagate

to all the action clients (see Figure 5) and when the action is disabled, all the

action clients instantly disable.

Figure 5: The application with actions

Also, these other controls use more of the action's properties. For example, when

a TMenuItem in the Menu Designer is connected to the action, the

ShortCut property is copied along with Checked, ImageIndex

and GroupIndex. In the VCL app, to make sure the menu item's ImageIndex

had something to index into both the popup menu and main menu were initially connected

to the same image list as the action list.

In the case of a VCL TToolButton, the action's Checked

property

value is copied to the Down property but most of the others go

through to the correspondingly named property. Tool buttons also have an ImageIndex

property so the toolbar was also connected to the image list in advance of connecting

the toolbutton to the action.

The FMX TSpeedButton does not have a Down

property and doesn't seem to absorb the action's Checked property

and, again, FMX actions do not yet support images.

One important point about a VCL tool button is worth making. Having connected the

toolbar

to the image list, the first tool button added to the toolbar will automatically

display the action's image. This is just coincidental. The first toolbutton gets

an ImageIndex of 0 automatically, the second gets an ImageIndex

of 1 and so on. The toolbutton will still need to be connected to the action like

any other action client.

You should be able to see the main point of action components now. Being automatically validated they give a smooth, reactive user interface with consistency amongst controls that invoke the same functionality.

When writing shared event handlers in applications that do not use actions, it is

common to use the Sender parameter as a means of identifying which

UI control triggered the event, so that specific code can execute when some specified

control triggers it. When using actions, the Sender parameter of the

OnExecute event handler that is propagated around will be the action

itself, not the UI control. Delphi 6 added the ActionComponent property

to all actions, which is set to the action client just before OnExecute

is fired and set back to nil afterwards.

The final iteration of this project is ActionApp3.dpr. This project shows the more modern way of building up a UI like the one in Figure 5 taking advantage of ActionBands. This is a VCL-only project as, at the time of writing, ActionBands are restricted to the VCL; they are not supported by FM2.

From Delphi 6 you can dispense with action list components altogether and simply use an action manager, which allows you to create action components. However in this case we will start from the position we were at with ActionApp.dpr and make use of the existing action list.

These

additional action components are sat at the end of the Additional page of

the

Component Palette. The TActionManager component is the enhanced action

list replacement that we will use here. You can also find the Action Band components,

TActionMainMenuBar, TPopupActionBar and TActionToolBar.

As you can probably guess, the TActionMainMenuBar and TActionToolBar

are specialised versions of a menu bar and a tool

bar respectively (the TPopupActionBar is a descendant of the regular

TPopupMenu). They allow you to very easily set up the UI for your actions

using

a drag and drop approach between the action manager's customisation dialog and the

action band components. They also allow you to easily specify the style that the

components will use; you can choose between standard (the Windows 98/2000 style)

and XP (the Windows XP style). Another component you will find on the Additional

page is TCustomizeDlg, which provides users with a runtime equivalent

of the action manager's design-time configuration dialog, thereby making it very

straightforward for users to customise their menu and toolbars.

To build our action application with the new components, proceed as follows. Drop

a TActionManager on the form and connect it to the image list already

on the form using its Images property. Double-clicking on the action

manager invokes its customisation dialog where new actions can be added (amongst

other features), but before we go there, we need to hook up to the existing action

list component.

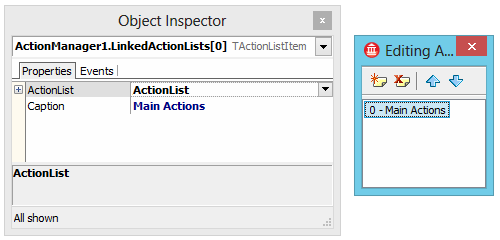

The property LinkedActionLists is a TLinkedActionListCollection

object that represents a collection of references to action lists in your application.

Press the button next to this property to invoke the collection editor and then

either press the Insert key or the yellow button to add a TActionListItem

item to the collection. The Object Inspector will show that this collection item

has just two properties. The ActionList property allows you to connect

it to the action list component, and the Caption property allows you

to give it a user-friendly name, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Connecting an action manager to an existing action list

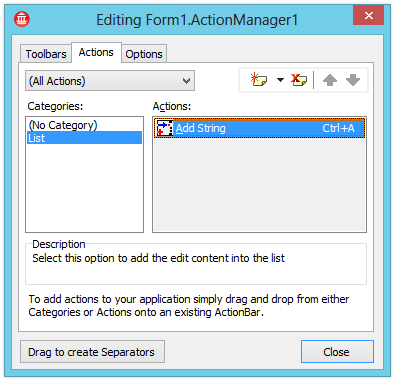

With this step done, you can double-click the action manager component to see its

customisation dialog, where you can see all the actions defined in our action list

(which in this example amounts to a single action) as shown in Figure 7. At this

point, it might be wise to specify a category for our sole action to make things

more intuitive later. Select the action in the action manager dialog, and on the

Object Inspector set the Category property to List.

Figure 7: Seeing all the actions under the action manager's control

With the action manager prepared, it is time to add one of the action bands to the form.

Get a TActionMainMenuBar from the Additional page of the

Component Palette and place it on the form. To make the action manager fully aware

of it, select the action manager component, then select its ActionBars

property on the Object Inspector. Press the ellipsis button to bring up the ActionBars

collection editor and press the Insert key to make a new ActionBar

collection item. Use the ActionBar property to link it to your action

menu bar component. However this step is actually not required, as the link will

be made implicitly as soon as you start adding items to the Action Bar (action main

menu bar or action toolbar) as described below.

To get an action-aware toolbar, you can pick a TActionToolBar from

the Component Palette and use the same approach to tell the action manager about

it. Alternatively, you can switch to the action manager dialog's Toolbars

tab and press the New button.

Note: this page of the dialog also allows you to customise the tooltip settings used on the toolbars, although there was a bug in this area prior to Delphi 6 Update Pack 2.

To set up the menu bar and the toolbar

you drag the single action from the action manager

dialog's Actions tab onto the toolbar. You can also drag the whole List

category of actions onto the menu bar. This adds a List menu on the

menu bar, with menu items for each action in the category hanging off it. Figure

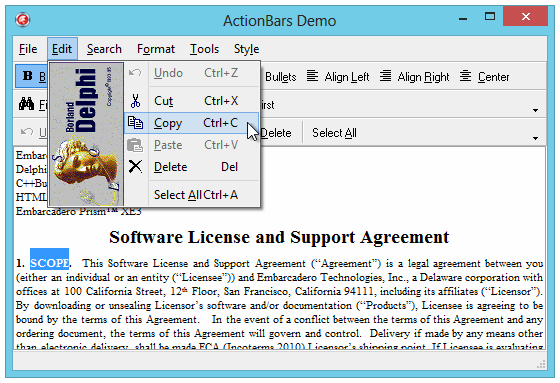

8 shows the action main menu bar being used, thereby temporarily obscuring the action

toolbar just below it.

Figure 8: An ActionBand in use

In Delphi 7 and later you can readily switch the style that the Actionbands components

display with. You do this with the action manager's Style property,

which by default offers three values these days: Standard, XP Style

and the more recent Platform Default.

It defaults to XP Style and so the menus take on an XP look and feel.

The sample Actionbands application in Delphi's Demos\ActionBands is called WordPad.dpr

and this has a Style menu that allows you to dynamically switch between

the styles, as well as enable or disable shadows drawn behind the menus.

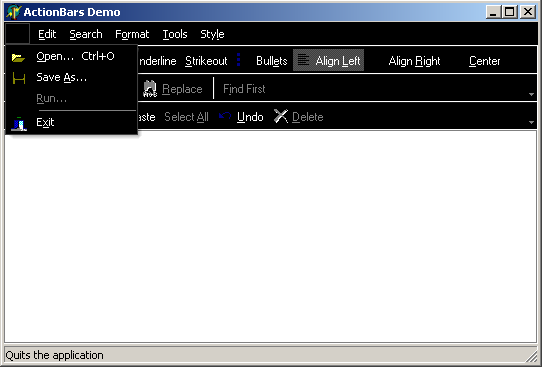

You can see the difference between the styles here. Figure 9 shows this sample application using the standard style:

Figure 9: The standard ActionBands style

Figure 10 shows the effect of enabling the XP style. You can see the more colourful menu with the column for the menu icons. You can also see that toolbuttons have a different appearance when they are selected.

Figure 10: The XP ActionBands style

The general ActionBands style can be enhanced further using colour maps (introduced

in Delphi 7). Each ActionBand component has a ColorMap property (a

subcomponent property of type TCustomActionBarColorMap) that allows

you to customise any of the colours used in drawing various parts of it. You can

also make use of three colour map components that are supplied on the Additional

page of the Component Palette: TStandardColorMap, TXPColorMap

and TTwilightColorMap. These components define the default colours

used by the standard and XP styles as well as a set of colours that give your application

the same look and feel as the now defunct Microsoft Encarta encyclopaedia.

Note: I'd approach the colour maps with caution as my simple test in Delphi XE3 didn't have good results. The action bars currently seem to ignore the colour map font colour when running on my Windows 8 and so I don't see any text. [BUG?]

Figure 11: The twilight (Encarta) colour map (compiled and running in Delphi 7)

Making life easy for setting up menus and toolbars full of action clients is not

the end of what Action Bands offer. Over and above the general UI style and colours

that we saw above that we can change, you can customise

the appearance of an action toolbar or any of its toolbuttons, as well as the main

menu bar, and also each individual menu that hangs off it. For example, if you have

an action menu bar with a File and a Help menu, you can

customise the main menu bar, as well as the File menu and the Help

menu.

The customisation on offer is quite impressive, matching the sorts of things Microsoft

once did in their own applications, though it's probably safe to say that much

of these capabilities make things look a little dated now. You can change the colour

or supply a background

bitmap to start with, which can optionally be stretched or tiled. This bitmap can

also be used as a banner, laid down the right side (of a menu for example) or up

the left side (rather like the Windows XP Start menu).

For example, Figure 12 shows the same application as before with the main menu bar and sporting a background bitmap.

Note: I did actually try and set the action toolbar to use a different background colour, but it failed to work correctly at runtime, a bit like the text colour. While it looked ok in the form designer, it reverted to the default menu colour at runtime. [BUG?]

Figure 12: Customised Action Bands

Setting up these modifications is straightforward as they are all attributes of

the action manager's ActionBars collection items (TActionBarItem

objects). Bring up the collection editor for the ActionBars property

and select the top level action bar you are interested in. The Object Inspector

will show you the properties you need to use, including Background,

BackgroundLayout and Color (though as previously noted,

you'll need to test carefully to ensure things work at runtime as expected). To

get to individual menus

or submenus, use the Items property, which is a TActionClients

collection, containing TActionClientItem objects. This has a similar

set of properties, including Items for going down to further levels.

Note: as well as Items, there is also a ContextItems

collection property. You can add new items to this collection (using the collection

property editor or the Object TreeView) and connect them up to any action you choose

using the Object Inspector. These context items will automatically appear in a popup

menu when you right click on the relevant Action Bar.

Figure 13 shows the Borland demo project for Action Bands with a modified menu bar

and Edit menu. As you can see, it uses a bitmap as a left-hand menu

banner and also uses a tiled bitmap as a menu bar background. This was achieved

as follows:

ActionBars propertyItems propertyBackground and BackgroundLayout properties as

you choose. Note that the background image only seems to be used if it's a bitmap

image

(GIF and PNG don't appear to work) and that only the left banner layout value

seems to be respected [BUG?].Figure 13: The Action Bands demo project with a menu banner bitmap

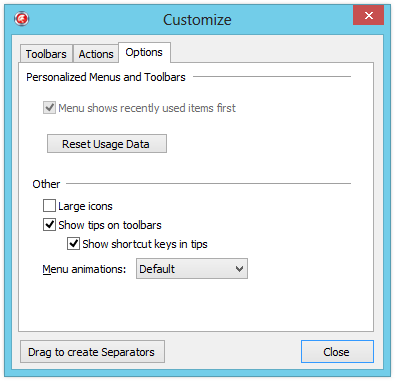

Personalized menus (sometimes known as IntelliMenus) were introduced in Windows 2000 and were also supported in Windows XP and versions of Office from around the same time. They involve having the more frequent menu items in a menu rising to the top of the menu and the less frequently used menu items being hidden away in a collapsed menu section, but being accessible by clicking the collapsed section on the double arrow that represents it.

Action bands support these usage-aware as you can see in Figure 14.

Figure 14: A menu with some items hidden through lack of use

Figure 15 shows what you get if you hold your mouse over that menu item, or click on it.

Note: this usage support is automatic, and operates through a number

of properties. To determine when to display or hide a UI element that is rendered

by the action band for a specific TActionClientItem, the action manager

maintains a count for each item of the total number of sessions it has been used

in (TActionClientItem.UsageCount), the last session number it was used

in (TActionClientItem.LastSession), and the current session number

(TActionBars.SessionCount). The number of sessions is defined as the

number of times the application has been launched.

This information is then tallied against a reference table, stored in the action

manager's PrioritySchedule property. To determine if an item should

be displayed, the program looks up the value of UsageCount in the left

hand column in PrioritySchedule. The corresponding value in the right

hand column is the number of sessions an item can be unused before it becomes hidden.

If it has not been used in that many sessions, it becomes hidden.

Figure 15: All menu items are visible now

Setting the UsageCount property of a TActionClientItem

to -1 will ensure it is always shown. To disable this facility altogether, clear

all the values from the PrioritySchedule property.

Note: Windows Vista dropped support for personalized menus and Office also followed by removing support for them. The appeal of them apparently wasn't so great after all. Consequently making use of this menu functionality is probably not wise.

Note: It would appear that at some point in time between Delphi 7 and Delphi XE2 the VCL broke its support for them. All the properties and methods are still there. However the option to enable or disable them on the Options tab of the Action Manager customisation dialog stays disabled (see Figure 16). This appears to be because it is only enabled if there is an action menu bar in the list of toolbars on the Toolbars tab of the dialog. However you can only add action toolbars in the list. Additionally, and perhaps more importantly, I found some disturbing issues when running the WordPad action bands sample (from Delphi XE3) on Windows XP. On first view of the menus all looks well, but when moving the mouse back over the menus most of the menu items had completely disappeared! I haven't spent too much time folloing this up, given the suggestion to ignore usage-aware menus, but be warned! [BUG?]

Figure 16: The personalized menus option is disabled

It has been mentioned that the action manager dialog can be made available at runtime.

This can be done in one of two ways. You can add a TCustomizeDlg to

a form, set its ActionManager property appropriately and call its

Show method. Alternatively you can use the pre-supplied TCustomizeActionBars

standard action. We will look more at how standard actions are accessed and used

in the next section.

As your users make modifications to their menus and toolbars using the customisation

dialog, you will almost certainly want all their settings to be saved to disk between

sessions. This is easily accommodated using the action manager's FileName

property. When the application starts up, the action manager will read all the settings

from the file, and when the application is being terminated, all the settings are

written back to it.

There is a lot of nice functionality on offer in the ActionBands classes that evades

observation on first glances. One example can be found in the ActionBars

property, which is an object that manages all the action bar items. Recall that

an action bar item links the Action Manager to an Action Bar and also manages the

action client items on the Action Bars). Whilst the help doesn't directly mention

it, there is a useful method called IterateClients available in ActionBars

(inherited from the ancestor TActionClientsCollection class).

This routine allows you to recursively execute a specified callback method against

every action client item in a specified action client collection. This means you

can have code execute against every item that sits on an Action Bar connected to

an Action Manager using simple code such as in Listing 4. IterateClients

takes a TActionClientsCollection object (such as an Action Manager's

ActionBars property) and proceeds to iterate through all the action

clients (TActionClientItem or TActionBarItem objects)

it finds.

Note: IterateClients will locate action clients found

in Items action client collections but does not look in the ContextItems

properties.

Listing 4: Iterating over all action clients

procedure TForm1.ActionCallBack(AClient: TActionClient); begin if AClient is TActionClientItem then ListBox1.Items.Add(TActionClientItem(AClient).Caption) end; procedure TForm1.Button1Click(Sender: TObject); begin ListBox1.Clear; ActionManager1.ActionBars.IterateClients( ActionManager1.ActionBars, ActionCallBack); end;

If you take the time to browse through the ActionBands source you will find plenty

of other goodies. You can get a good demonstration of all the general ActionBands

options by opening up the demo projects that come with Delphi, which can be found

in Delphi\VCL\ActionBands and its subdirectories under the Samples directory. Figure

13

shows that demo running after I added a left banner image to one of the menus. Other

demo apps (added in Delphi 7) to

be found there show you how to build an MRU (most recently

used) menu (like Delphi's File | Reopen menu), how to dynamically create

ActionBand components, and how to use alpha-blending in ActionBand menus.

The actions that we have been manually setting up are sometimes called custom actions, since the Delphi developer customises their behaviour and properties. Delphi also comes with quite a number of pre-defined actions with built-in behaviour and property values, which are referred to as standard actions, so named since their behaviour and attributes are supplied with Delphi as standard.

These standard actions provide commonly useful behaviour, such as clipboard interaction, MDI window commands and help commands. Table 1 shows the standard VCL actions that are supplied with Delphi and Table 2 shows the standard FMX actions.

Table 1: Standard VCL actions available in Delphi

| Standard action class name | Defined in | Category | Purpose |

TEditCut

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Edit | cuts highlighted text from the target to the Clipboard |

TEditCopy

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Edit | copy highlighted text to the Clipboard |

TEditPaste

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Edit | pastes text from the Clipboard to the target and ensures that the Clipboard is enabled for the text format |

TEditSelectAll

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Edit | selects all the text in the target edit control |

TEditUndo

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Edit | undoes the last change made to the target edit control |

TEditDelete

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Edit | deletes the highlighted text |

TRichEditBold

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Format | toggles the bold attribute of the currently selected text in a rich edit control |

TRichEditItalic

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Format | toggles the italic attribute of the currently selected text in a rich edit control |

TRichEditUnderline

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Format | toggles the underline attribute of the currently selected text in a rich edit control |

TRichEditStrikeOut

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Format | toggles the strike-out attribute of the currently selected text in a rich edit control |

TRichEditBullets

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Format | toggles whether the current paragraph in a rich edit control is bulleted |

TRichEditAlignLeft

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Format | left-justifies the text in the current paragraph of a rich edit control |

TRichEditAlignRight

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Format | right-justifies the text in the current paragraph of a rich edit control |

TRichEditAlignCenter

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Format | centres the text horizontally in the current paragraph of a rich edit control |

THelpContents

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Help | brings up the Help Topics dialog on the tab (Contents, Index or Find) that was last used |

THelpTopicSearch

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Help | brings up the Help Topics dialog on the Index tab |

THelpOnHelp

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Help | brings up the Microsoft help file on how to use Help |

THelpContextAction

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Help | brings up the help topic for the active control |

TWindowClose

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Window | closes the active MDI child form |

TWindowCascade

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Window | cascades the MDI child forms |

TWindowTileHorizontal

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Window | arranges MDI child forms so that they are all the same size, tiled horizontally |

TWindowTileVertical

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Window | arranges MDI child forms so that they are all the same size, tiled vertically |

TWindowMinimizeAll

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Window | minimises all of the MDI child forms |

TWindowArrange

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Window | arranges the icons of minimised MDI child forms |

TFileOpen

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | File | displays a file open dialog |

TFileOpenWith

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | File | display dialog that lets users choose what application to user for opening a file |

TFileSaveAs

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | File | displays a file save as dialog |

TFilePrintSetup

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | File | displays a print setup dialog |

TFilePageSetup

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | File | displays a page setup dialog |

TFileRun

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | File | launches an application, or performs some other registered file operation |

TFileExit

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | File | terminates the application |

TBrowseForFolder |

Vcl.StdActns.pas | File | displays the folder browse dialog |

TSearchFind

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Search | displays a find dialog |

TSearchFindFirst

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Search | displays a find dialog that looks for the first string |

TSearchReplace

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Search | displays a find-and-replace dialog |

TSearchFindNext

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Search | locates the next instance of a string in an appropriate control |

TPreviousTab

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Tab | moves a page/tab control to the previous tab |

TNextTab

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Tab | moves a page/tab control to the next tab |

TListControlCopySelection

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | List | copies selected items in a list control (listbox or list view) to another list control |

TListControlDeleteSelection

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | List | deletes all selected items in a list control |

TListControlSelectAll

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | List | selects all items in a list control |

TListControlClearSelection

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | List | deselects all items in a list control |

TListControlMoveSelection

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | List | moves selected items in a list control (listbox or list view) to another list control |

TStaticListAction

|

Vcl.ListActns.pas | List | provides items to client list controls |

TVirtualListAction

|

Vcl.ListActns.pas | List | provides items to client list controls |

TOpenPicture

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Dialog | displays the open picture dialog |

TSavePicture

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Dialog | displays the save picture dialog |

TColorSelect

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Dialog | displays the colour section dialog |

TFontEdit

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Dialog | displays the font edit dialog |

TPrintDlg

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | Dialog | displays the print dialog |

TBrowseURL

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Internet | launches the default browser to display a specified URL |

TDownLoadURL

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Internet | saves contents of a specified URL to a file |

TSendMail

|

Vcl.ExtActns.pas | Internet | sends an email message |

TDataSetFirst

|

Vcl.DbActns.pas | Dataset | sets the current record to the first record in the dataset |

TDataSetPrior

|

Vcl.DbActns.pas | Dataset | sets the current record to the previous record |

TDataSetNext

|

Vcl.DbActns.pas | Dataset | sets the current record to the next record |

TDataSetLast

|

Vcl.DbActns.pas | Dataset | sets the current record to the last record in the dataset |

TDataSetInsert

|

Vcl.DbActns.pas | Dataset | inserts a new record before the current record, and sets the dataset into

dsInsert

state so it can be modified

|

TDataSetDelete

|

Vcl.DbActns.pas | Dataset | deletes the current record and makes the next record (if there is one, otherwise the previous record) the current record |

TDataSetEdit

|

Vcl.DbActns.pas | Dataset | puts the dataset into dsEdit state so that the current record can be

modified

|

TDataSetPost

|

Vcl.DbActns.pas | Dataset | writes changes in the current record to the dataset |

TDataSetCancel

|

Vcl.DbActns.pas | Dataset | cancels the edits to the current record, restores the record display to its condition

prior to editing, and turns off dsInsert or dsEdit states

if they are active

|

TDataSetRefresh

|

Vcl.DbActns.pas | Dataset | refreshes the buffered data in the associated dataset by calling its Refresh

method

|

TClientDataSetApply

|

Vcl.DbClientActns.pas | DataSnap Client | applies the updates in a client dataset's change log |

TClientDataSetRevert

|

Vcl.DbClientActns.pas | DataSnap Client | back out all changes in a client dataset's current record |

TClientDataSetUndo

|

Vcl.DbClientActns.pas | DataSnap Client | back out the last edit to a client dataset's current record |

TBindNavigateFirst

|

Vcl.Bind.Navigator.pas | LiveBindings | sets current record to be first record in LiveBindings data source |

TBindNavigatePrior

|

Vcl.Bind.Navigator.pas | LiveBindings | sets current record to be previous record in LiveBindings data source |

TBindNavigateNext

|

Vcl.Bind.Navigator.pas | LiveBindings | sets current record to be next record in LiveBindings data source |

TBindNavigateLast

|

Vcl.Bind.Navigator.pas | LiveBindings | sets current record to be last record in LiveBindings data source |

TBindNavigateInsert

|

Vcl.Bind.Navigator.pas | LiveBindings | insert a new record in LiveBindings data source |

TBindNavigateDelete

|

Vcl.Bind.Navigator.pas | LiveBindings | delete record from LiveBindings data source |

TBindNavigateEdit

|

Vcl.Bind.Navigator.pas | LiveBindings | put LiveBindings data source into edit mode |

TBindNavigatePost

|

Vcl.Bind.Navigator.pas | LiveBindings | write changes in current record to LiveBindings data source |

TBindNavigateCancel

|

Vcl.Bind.Navigator.pas | LiveBindings | cancel edits in current record of LiveBindings data source and leave edit/insert mode |

TBindNavigateRefresh

|

Vcl.Bind.Navigator.pas | LiveBindings | refresh current record from LiveBindings data source |

TBindNavigateApplyUpdates

|

Vcl.Bind.Navigator.pas | LiveBindings | apply all pending updates to LiveBindings data source |

TBindNavigateCancelUpdates

|

Vcl.Bind.Navigator.pas | LiveBindings | cancel all pending updates to LiveBindings data source |

TCustomizeActionBars

|

Vcl.BandActn.pas | Tools | causes the Action Bands customisation dialog to appear |

THintAction

|

Vcl.StdActns.pas | None | First documented in Delphi 6 as a way of displaying custom hints in the same way

as done by TStatusBar.AutoHint.

|

Table 2: Standard FMX actions available in Delphi

| Standard action class name | Defined in | Category | Purpose |

TVirtualKeyboard |

FMX.StdActns | Edit | shows an on-screen keyboard |

TWindowClose

|

FMX.StdActns | Window | close the active window |

TFileExit

|

FMX.StdActns | File | exit app |

TFileHideApp

|

FMX.StdActns | File | |

THideAppOthers

|

FMX.StdActns | File | |

TViewAction |

FMX.StdActns | View | |

TFMXBindNavigateFirst

|

Fmx.Bind.Navigator | LiveBindings | sets current record to be first record in LiveBindings data source |

TFMXBindNavigatePrior

|

Fmx.Bind.Navigator | LiveBindings | sets current record to be previous record in LiveBindings data source |

TFMXBindNavigateNext

|

Fmx.Bind.Navigator | LiveBindings | sets current record to be next record in LiveBindings data source |

TFMXBindNavigateLast

|

Fmx.Bind.Navigator | LiveBindings | sets current record to be last record in LiveBindings data source |

TFMXBindNavigateInsert

|

Fmx.Bind.Navigator | LiveBindings | insert a new record in LiveBindings data source |

TFMXBindNavigateDelete

|

Fmx.Bind.Navigator | LiveBindings | delete record from LiveBindings data source |

TFMXBindNavigateEdit

|

Fmx.Bind.Navigator | LiveBindings | put LiveBindings data source into edit mode |

TFMXBindNavigatePost

|

Fmx.Bind.Navigator | LiveBindings | write changes in current record to LiveBindings data source |

TFMXBindNavigateCancel

|

Fmx.Bind.Navigator | LiveBindings | cancel edits in current record of LiveBindings data source and leave edit/insert mode |

TFMXBindNavigateRefresh

|

Fmx.Bind.Navigator | LiveBindings | refresh current record from LiveBindings data source |

TFMXBindNavigateApplyUpdates

|

Fmx.Bind.Navigator | LiveBindings | apply all pending updates to LiveBindings data source |

TFMXBindNavigateCancelUpdates

|

Fmx.Bind.Navigator | LiveBindings | cancel all pending updates to LiveBindings data source |

You create standard actions from either the action list editor or the action manager's

customisation dialog. However, instead of pressing the yellow button, you should

drop down the arrow next to it and choose New Standard Action... from

the drop down menu (or press Ctrl+Insert). This takes you to a dialog

that lists all available standard actions (see Figure 17).

Figure 17: The standard action choice dialog

If an action list or action manage exists on the form, you can also create a new

standard action that is automatically associated with an action client control by

going to the control in question and choosing New Standard Action

from the Action property's dropdown editor. In Figure 18 a

new standard action is being added to an action list called ActionList

on the

form (it could equally be added to the action manager called ActionManager1).

This new action will be connected to the currently selected control.

Figure 18: Another way to create a standard action

Assuming you have an image list associated with your action list, when a standard

action is created it will add its associated image into your image list and set

its ImageIndex property to the position of it, assuming it has one.

It also sets up its other property values to pre-defined values (see Figure 19).

However I think it's fair to say that the set of default action images is long

overdue for an overhaul to make to look current and up to date.

Figure 19: Instances of each of Delphi's standard actions

Some of these standard actions have an additional property that can be used to specify

a dedicated target control. For example, all the dataset actions have a published

DataSource property that appears on the Object Inspector. You can optionally

use this property to connect the actions to one specific data source component but,

again, this is not required. If you leave the property blank, the magic of action

handling will allow the action to find the first data source on the active form

at run-time.

Similarly all the standard edit actions have a public Edit property

and the standard window actions have a Form public property. You can

therefore programmatically tie an edit action to a fixed edit control, or a window

action to one specific form. But if you do not, the edit action will act on the

active edit control (if there is one) and the window action will act on the active

MDI form (if there is one).

Some action components manage their own extra components on your behalf,

without requiring you to set up your own. For example, the TFileOpen

standard action manages its own internal open dialog

component, whose properties you can see by expanding its Dialog property.

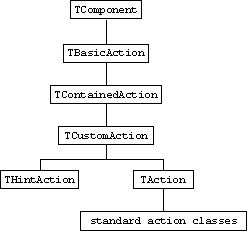

There are a lot of classes associated with actions and so, rather than simply listing them out, I will try and give an overview that encompasses them all. If you have no desire to know more about the internal workings of actions or of how to make reusable standard actions, you should perhaps skip the rest of this article. It is dirty-hand territory from here on in.

The action class hierarchy (see Figure

20) starts with TBasicAction

from System.Classes

(see Listing 5) which can be used in conjunction with an action client that is neither

a menu nor a control. TContainedAction (from System.Actions) adds support

to allow an action

to appear in an action list. It also adds the published Category property

to

allow actions to be categorised and the UI properties

that can be propagated to action clients such as menus and controls, which are

not published. TCustomAction (Vcl.ActnList or Fmx.ActnList) adds in

the image list support

(in the case of the VCL) and adds in the awareness of action lists and TAction

(also in Vcl.ActnList

and Fmx.ActnList) publishes all the interesting

properties of TCustomAction.

Listing 5: The TBasicAction base action class

TBasicAction = class(TComponent) private FClients: TList; [Weak] FActionComponent: TComponent; FOnChange: TNotifyEvent; FOnExecute: TNotifyEvent; FOnUpdate: TNotifyEvent; function GetClientCount: Integer; function GetClient(Index: Integer): TBasicActionLink; procedure SetActionComponent(const Value: TComponent); protected procedure Change; virtual; procedure SetOnExecute(Value: TNotifyEvent); virtual; property OnChange: TNotifyEvent read FOnChange write FOnChange; procedure Notification(AComponent: TComponent; Operation: TOperation); override; property ClientCount: Integer read GetClientCount; property Clients[Index: Integer]: TBasicActionLink read GetClient; public constructor Create(AOwner: TComponent); override; destructor Destroy; override; function HandlesTarget(Target: TObject): Boolean; virtual; procedure UpdateTarget(Target: TObject); virtual; procedure ExecuteTarget(Target: TObject); virtual; function Execute: Boolean; dynamic; procedure RegisterChanges(const Value: TBasicActionLink); procedure UnRegisterChanges(const Value: TBasicActionLink); function Update: Boolean; virtual; property ActionComponent: TComponent read FActionComponent write SetActionComponent; property OnExecute: TNotifyEvent read FOnExecute write SetOnExecute; property OnUpdate: TNotifyEvent read FOnUpdate write FOnUpdate; end;

Figure 20: The action class hierarchy

You will notice that THintAction is also sitting in the hierarchy (and

was listed in Table 1). This class has been around since Delphi 4, but was first

documented in Delphi 6. You can use THintAction to display component

hints as the mouse moves around a form. TStatusBar uses this approach

in order to implement its AutoHint property.

Whilst apparently changing the subject, but not really, I will talk briefly about

data aware controls. Data aware controls and data source components appear to be

directly connected through the data aware controls' DataSource property.

However this is not actually the case. Instead, data link objects are employed in

any data aware control that implements a DataSource property to act

as the liaison officer, to represent the link to the dataset and to respond to data

events. Similarly, action clients that implement an Action property

use action link objects to connect action components to their properties (such as

Caption, Hint and ShortCut).

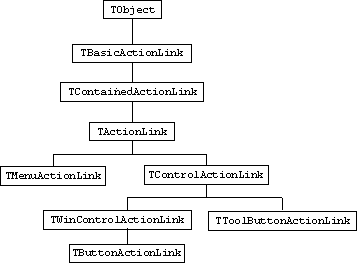

Action links exist as various classes in a mini-hierarchy (see Figure 21) with

TBasicActionLink at the root (see Listing 6). This class takes the client

object as a constructor parameter (although it does not store it) and the related

action is available as the Action property. It sets up the basic structure

of a connection between an action and a client. It defines virtual Execute

and Update methods which call the associated action's Execute

and Update methods. If the action has an OnExecute event

handler, Execute returns True and if it has an OnUpdate

handler, Update returns True. It also has an OnChange

event triggered when the properties of the action change.

Figure 21: The action link class hierarchy

Listing 6: The TBasicActionLink base action link class

TBasicActionLink = class(TObject) private FOnChange: TNotifyEvent; [Weak] FAction: TBasicAction; protected procedure AssignClient(AClient: TObject); virtual; procedure Change; virtual; function IsOnExecuteLinked: Boolean; virtual; procedure SetAction(Value: TBasicAction); virtual; procedure SetOnExecute(Value: TNotifyEvent); virtual; public constructor Create(AClient: TObject); virtual; destructor Destroy; override; function Execute(AComponent: TComponent = nil): Boolean; virtual; function Update: Boolean; virtual; property Action: TBasicAction read FAction write SetAction; property OnChange: TNotifyEvent read FOnChange write FOnChange; end;

TContainedActionLink adds in basic support for managing the connection

between

an action's properties and the action client properties (see Listing 7). It has

elementary support for Caption, Checked, Enabled,

GroupIndex, HelpContext, HelpKeyword, Hint,

ImageIndex (in the VCL), ShortCut

and Visible. The IsXXXXLinked methods all return True

if Action has been assigned a TCustomAction or descendant

whilst the SetXXXX methods do nothing. TActionLink

is a shallow descendant of TContainedActionLink that adds nothing

to it.

A TContainedActionLink or a TActionLink

can

be used as a base class for an action link that can be used when the action client

is neither a control nor a menu (which are catered by descendant action link classes).

Listing 7: The TActionLink class

/// This class is designed to communicate with some of the object. /// It implements to work with common properties for all platforms (FMX, VCL). TContainedActionLink = class(TBasicActionLink) protected procedure DefaultIsLinked(var Result: Boolean); virtual; function IsCaptionLinked: Boolean; virtual; function IsCheckedLinked: Boolean; virtual; function IsEnabledLinked: Boolean; virtual; function IsGroupIndexLinked: Boolean; virtual; function IsHelpContextLinked: Boolean; virtual; function IsHelpLinked: Boolean; virtual; function IsHintLinked: Boolean; virtual; function IsImageIndexLinked: Boolean; virtual; function IsShortCutLinked: Boolean; virtual; function IsVisibleLinked: Boolean; virtual; function IsStatusActionLinked: Boolean; virtual; procedure SetAutoCheck(Value: Boolean); virtual; procedure SetCaption(const Value: string); virtual; procedure SetChecked(Value: Boolean); virtual; procedure SetEnabled(Value: Boolean); virtual; procedure SetGroupIndex(Value: Integer); virtual; procedure SetHelpContext(Value: THelpContext); virtual; procedure SetHelpKeyword(const Value: string); virtual; procedure SetHelpType(Value: THelpType); virtual; procedure SetHint(const Value: string); virtual; procedure SetImageIndex(Value: Integer); virtual; procedure SetShortCut(Value: System.Classes.TShortCut); virtual; procedure SetVisible(Value: Boolean); virtual; procedure SetStatusAction(const Value: TStatusAction); virtual; end;

TMenuActionLink adds specific support for menu item clients by overriding

AssignClient (which stores the client in a private data field) and

IsOnExecuteLinked from Listing 6 as well as all the virtual methods

in Listing 7. This allows actions to map their UI properties to equivalent menu

item properties and their OnExecute to menu items' OnClick

events. TControlActionLink does a similar job for generic

controls, although it only skips some of the action properties, leaving those to

descendant classes.

The other action link classes add support for various other specific properties

of their indented client controls. For example TToolButtonActionLink

works with tool buttons, adding a link between the action's Checked

property and the tool button's Down property (note the difference in

name).

Being aware of action links and how they fit in is generally useful, however getting down to the nitty-gritty of how they operate is only important if you wish to write interesting new components with new properties that you want controlled by actions. Given that we will not be covering that subject in this article, it is safe to leave action links alone now.

Now that we have seen the basic use of actions and had an overview of the classes involved, let's look in more detail at how they work inside a Delphi application. On our travels you will see that the engineers who developed actions have provided many points that can be used to hook into action functionality. The execution path of actions presented here will be quite detailed, to give a full understanding of what goes on.

Action is defined as a public property in TControl (it

is published by a number of descendant classes) and a published property in TMenuItem.

When you assign an action component to an action client's Action property

the following sequence of events occurs.

In the case of a control, csActionClient is added to its ControlStyle

set property. Then if there is no action link object present already it creates

an action link using

the class reference returned by the protected dynamic GetActionLinkClass

method. This returns an appropriate action link class of which an instance is created.

The action link is given the action object and its OnChange event is

handled by a method that copies the key action properties to the

action client properties. Since the action has just been set, this routine (a protected

dynamic procedure called ActionChange) is triggered to get the current

action properties copied across. At this point, the client has got the action properties

and an appropriate action link object.

Now we need to see what happens when an action is invoked. Remember this can happen

by an action client invoking it, such as a button being clicked, or by any piece

of code calling the action's Execute method. It can also happen by

the user pressing the shortcut key associated with an action, which need not be

connected to any action client. By the end of this section we should be able to

see how each of these possibilities works.

We start by taking the case of an action client invoking the action, using an example

of a button hooked up to an action. When you look at a button set up as an action

client you can see the Object Inspector showing the OnClick event connected

to the action's OnExecute event handler. You might therefore understandably

think that clicking the button will simply call the action's OnExecute

handler. But it is not as simple as that. Oh no.

Instead, assuming the OnClick event has not been changed, the action

link's virtual Execute method is called (see Listing 8) with a parameter

equating to the action client (this becomes the action's ActionComponent

property for the duration of the OnExecute handler). The default implementation

of this in TBasicActionLink (which is not overridden in any of the

descendant classes) calls the action's dynamic Execute method. So at

this point the action client invoking the action now looks just the same as the

some code explicitly invoking an action by calling the Execute method.

Listing 8: The implementation of TControl.Click

procedure TControl.Click; begin { Call OnClick if assigned and not equal to associated action's OnExecute. If associated action's OnExecute assigned then call it, otherwise, call OnClick. } if Assigned(FOnClick) and (Action <> nil) and not DelegatesEqual(@FOnClick, @Action.OnExecute) then FOnClick(Self) else if not (csDesigning in ComponentState) and (ActionLink <> nil) then ActionLink.Execute(Self) else if Assigned(FOnClick) then FOnClick(Self); end;

The base action class

(TBasicAction) implementation of Execute tries to call

the action's

OnExecute event handler. Both Execute methods return

True if the handler exists and False if not. However TCustomAction

overrides Execute to perform more interesting logic. Since custom

actions can be managed by action lists, they broaden the potential for response

to an action by a wide margin.

Firstly, the action defers to its action list (if it has one) by calling its ExecuteAction

method and passing itself as a parameter. The action list's ExecuteAction

method is implemented to call its OnExecute event handler if

present. If the event handler sets its Handled parameter to True,

the story ends here. Otherwise it goes further.

Note: all the actions in an

action list will trigger the action list's OnExecute event handler

and so some generic handling or action tracking can be implemented there if needed.

Next, the Application object's OnActionExecute event is

triggered if present. Similarly, if the Handled parameter is set to

True, processing ends there, otherwise it carries on.

Note: the Application object's OnActionExecute

event will be triggered for all actions in the application that are not handled

by their corresponding action list, providing an option for completely general action

handling, or alternatively a way to intercept all actions not handled by their action

list.

If the action still has momentum, it at last tries to execute its own OnExecute

event handler. If no handler was set up, which will be the case for standard actions,

it goes still further. It packages itself up in a CM_ACTIONEXECUTE

message which gets sent to the Application object's window as a cry

for help in trying to find a target to execute against. The Application

object's message handler calls its DispatchAction method which tries

to locate a target on the active form and, failing that, the main form.

It does this by sending the same message to

the active form and then potentially the main form.

Each form then verifies that it is visible and if so, tries to find a target control.

Firstly, it checks whether the active control is a suitable target by passing the

action object to the control's ExecuteAction method. If not, the form

itself is tested to see if it might be a target, passing the action to its own

ExecuteAction method. If there is still no joy it calls ExecuteAction

for every visible control on the form, stopping if it finds a match.

The implementation of a component's ExecuteAction method typically

involves the component passing itself to the action's HandlesTarget

method. If this returns True, we have a suitable target and so the target is passed

to the action's ExecuteTarget method.

This way, an action target can be found for an action without the target knowing

anything about the action in advance. However, ExecuteAction can be

overridden to allow any control to pick up specific actions of interest, if needed,

without the action knowing about the target. It works both ways.

If the main form does not successfully handle the message then the final step is

reached. If the action is a TCustomAction (or inherited from that class),

is currently enabled, has no OnExecute handler and its DisableIfNoHandler

property is True, then the action is disabled. DisableIfNoHandler

is a public property defined by TContainedAction which defaults to

True.

TCustomAction also calls the virtual Update method to

update the action's state before setting off on this possibly lengthy trek to execute

the action. This ensures the action's state is up-to-date based upon the immediately

current state of the application before being executed.

As a bit of a contrast the FireMonkey action execution implementation is a

little more straightforward. There are various things that can't be done in the

same way with FireMonkey thanks to a lack of a message pasing model underlying

the framework. Consequently the TCustomAction.Execute has a rather

simpler implementation. After calling Update it checks

its Enabled property is True and then calls the Execute

inherited from TBasicAction. The implication of this is that

FireMonkey will not manage to locate an action target without it being connected

to it in some way. This presumably explains why there is a smaller set

of

standard actions available for FireMonkey at present.

The case with actions we have not looked at yet is where an action's shortcut key is pressed, causing the action to be invoked, regardless of whether an action client has been set up or not. Let's run through the VCL's logic first:

IsShortCut

method.OnShortCut event

or, failing that, through its main menu.Execute method is

called.

CM_APPKEYDOWN

message is sent to the Application object which calls its own IsShortCut

method.OnShortCut event

and if that fails it calls the main form's IsShortCut method.

This way a shortcut key can be picked up by an action on the active form or the

main form, assuming a menu item or OnShortCut event does not handle

it first.

Now let's consider the FMX logic for locating and executing an action that is not connected to an action client:

TCommonCustomForm.KeyDown

then

it tries to find something to handle it in the following order.

As you can see, the VCL goes to a lot of trouble to service actions if they do not

have an OnExecute event or even an action client, which standard actions

tend not to. It is this concerted search effort that enables standard actions to

work without necessarily being connected to an action client. They can typically

operate on the active control (or some other suitable control) on the active form

thanks to the VCL's in-built target-searching logic.

As mentioned, TCustomAction updates an action just before trying to

execute it. However, actions also get updated at another point in time. When a

VCL application

has processed all of its pending messages it transitions into an idle state. Windows

wakes it up when another message arrives. The same basic behaviour happens in

FireMonkey applications.

In the case of the VCL, this is the sequence of events that occurs:

Application

object's Idle method calls its OnIdle event handler and

then calls the DoActionIdle method.

DoActionIdle loops through all enabled forms on-screen calling

UpdateActions.UpdateActions calls the virtual InitiateAction method

for

the form itself, all top level,

visible menu items and then all visible controls with csActionClient

in ControlStyle (in other words all action clients).InitiateAction

calls the Update method of the action link, if there is one, which

calls

the action's Update method.

TBasicAction implementation of Update either

calls

OnUpdate if it exists and returns True, otherwise it returns

False.TCustomAction overrides Update

to do much the same sort of thing as with Execute. It checks to see

if the action list or Application object wishes to deal with updating

the action in their OnActionUpdate events. Then it tries its own

OnUpdate event handler.Application

object to help find a target control to update itself against.

The action is passed to each possible target's UpdateAction method

which calls HandlesTarget. If the action claims to handle the target

then the action's UpdateTarget method is called.

In an FMX app the sequence looks like this:

Application

object's Idle method calls DoIdleDoIdle triggers the OnIdle event, if present, passing

True as the value of the var parameter DoneDone is set to False then no action updating is performed, but if

Done is still True then the actions

will be updatedActionUpdateDelay property:

ActionUpdateDelay is 0 then actions will be updated immediately

ActionUpdateDelay is non-zero then the actions will execute after

a delay in

milliseconds equal to ActionUpdateDelayActionUpdateDelay has been set to ActionUpdateDelayNever

(-1) then action

updates will not occurDoUpdateActions

method. This calls UpdateActions on all active forms and then on all

inactive forms.TCommonCustomForm.UpdateActions gathers up a list of menu items and

controls on the form and calls their virtual TFmxObject.InitiateAction

method.InitiateAction

calls the Update method of the action link, if there is one, which

calls

the action's Update method.TBasicAction implementation of Update either

calls

OnUpdate if it exists and returns True, otherwise it returns

False.TCustomAction overrides Update to check

if the action list or Application object wishes to deal with updating

the action in their OnUpdateAction events. Then finally it calls

the inherited code and so tries its own OnUpdate event handler.

This all means that every time a user's input (key presses, mouse clicks, and so on) have been serviced and the program goes idle waiting for the next message, all actions connected to action clients are updated. Consequently, this means that the action clients always have an up-to-date representation of the action properties. Additionally, all actions (regardless of whether they are connected to clients or not) are updated just before they execute.

Because the CPU is so fast, the application will go idle between each key press and mouse click meaning that actions are updated very regularly. The implication of this is that you must ensure your action update code is not time-intensive to avoid having a sluggish application.

We have seen how to make custom actions and how to use standard actions, so now we turn our attention to making new standard actions of our own. The general idea is fairly straightforward although there are a few twists and turns here and there.

The goal is to inherit a class from TAction and override three methods.

HandlesTarget decides whether we handle a given target control. UpdateTarget

should check appropriate criteria and update the action properties if needed.

ExecuteTarget contains the code represented by the standard action. These

methods have all been mentioned before and are all defined as virtual in TBasicAction

where they do nothing except HandlesTarget, which returns False,

indicating nothing is handled.

If needed, the action can define a property to link it to a specific target component. If this is done you must be careful to hook into the standard notification mechanism so you are informed if the linked component is destroyed.

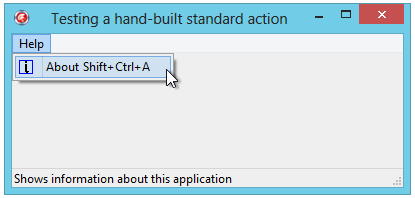

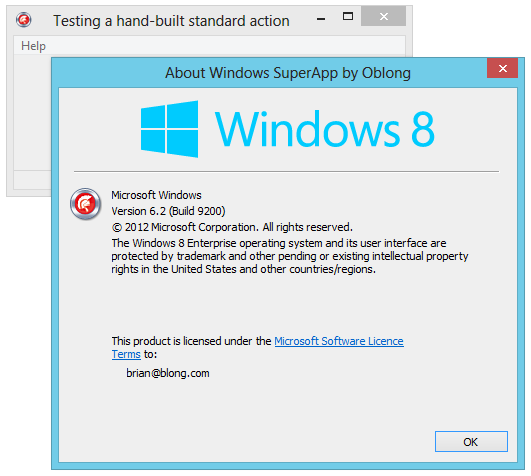

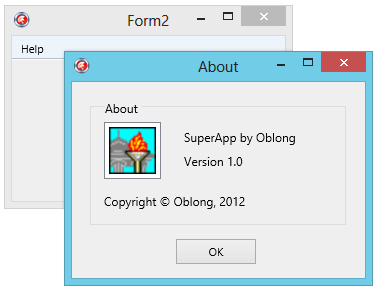

The standard action we will develop will be called THelpAbout and will

invoke an application About box. It will have a public property that allows it to

be connected to any form class in an application, which will be displayed modally

as the About dialog. Now, the job of this action is clearly not too ambitious; it

can readily be done in program code. However, wrapping functionality like this into

an action means that it can easily be invoked from both a menu and a toolbutton.

Incidentally, the reason the property allows connecting to a form class, rather than a form object is so that the About form does not have to be auto-created, or programmatically created in advance. The action can create the About form, display it and then free it. This also means that unlike when connecting to an object, we will not need to hook into the notification system to spot if the form gets destroyed behind our back.

Also, the reason this property is public rather than published is that the Object Inspector does not display class reference properties.

Note: if this property has not been assigned a form class, the action will use the standard Windows About box, as used by Windows Explorer, Notepad, Calculator, etc. Listing 9 shows the action's code.

Listing 9: The common base class for the standard actions

type THelpAbout = class(TAction) private FAboutClass: TCustomFormClass; protected procedure SetAboutClass(Value: TCustomFormClass); public function HandlesTarget(Target: TObject): Boolean; override; procedure UpdateTarget(Target: TObject); override; procedure ExecuteTarget(Target: TObject); override; property AboutClass: TCustomFormClass read FAboutClass write SetAboutClass; end; ... uses ShellAPI; { THelpAbout } procedure THelpAbout.ExecuteTarget(Target: TObject); var About: String; begin if Assigned(AboutClass) then with AboutClass.Create(Application) do try ShowModal finally Free end else begin About := 'Windows ' + Application.Title; ShellAbout(Application.MainForm.Handle, PChar(About), nil, Application.Icon.Handle) end end; function THelpAbout.HandlesTarget(Target: TObject): Boolean; begin //This action does not operate on any target controls, //so all proposed targets are acceptable Result := True end; procedure THelpAbout.SetAboutClass(Value: TCustomFormClass); begin if Value <> FAboutClass then FAboutClass := Value; end; procedure THelpAbout.UpdateTarget(Target: TObject); begin //Whether a custom about form class has been assigned or not, //this action will work (it uses the Windows About dialog if //no form class has been assigned) Enabled := True end;

This code can be found in AboutAction.pas, which has been added into the AboutAction.dpk run-time package. Don't forget to place the compiled package (the BPL file) in a directory on the path to allow Delphi to see it.

Apart from initialising its properties, the action is now ready to be registered. Typically, components perform property initialisation in their constructors. This would work fine for this action as well except for its associated image.

You may recall that standard actions can copy their image into the image list associated with their action list at design-time (see Figure 18 for a reminder). In order to allow our action to be just as friendly, we initialise its properties (image index, shortcut and so on) in a different way to normal components.

To register standard actions in the IDE, you call RegisterActions passing

a category, a list of action classes and optionally, a data module class. The data

module is used to pre-initialise the action properties and image. It works like

this.

You make a data module, then drop an image list onto it, which you fill with images

for your standard actions. Next, you place an action list on the data module and

hook it up to the image list. The idea is that you then use the Action List Editor

to create instances of your new standard actions whose properties you can initialise

as you like. This data module class is then passed as the third parameter to RegisterActions.

However, if you think about this, in order to get your standard actions created through the action list editor they must first be registered so the IDE knows about them. So what we can do is ignore the data module issue to start with and register the action on its own (we can worry about the data module later).

This is done with a normal IDE registration routine in a registration unit (AboutActnReg.pas),

as shown in Listing 10. Notice that nil is passed in place of the data

module class. The registration unit is added to a design-time package (DCLAboutAction.dpk)

which is compiled

and installed.

Listing 10: First time registration of an action

procedure Register; begin //The first-time registration to get the actions in the IDE, //but without initialised properties or an associated image //(which is the ImageIndex property) RegisterActions('Help', [THelpAbout], nil) end;

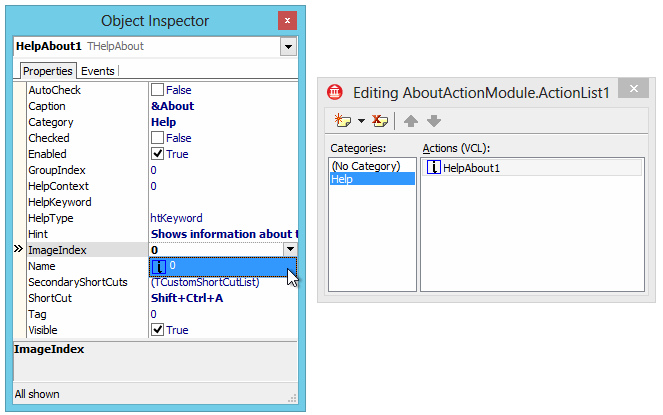

At this point the IDE knows about the new standard actions so the data module can now be set up. A suitable data module called AboutActionModule is in the unit AboutActionRes.pas, which should be added to the design-time package. The image list can now be set up to contain appropriate images and the action list can be added and connected to it.

The Action List Editor can now be used to create an instance of our new standard action, and its properties can be set as required. Figure 22 shows the action fully set up on the data module, with all its custom properties on the Object Inspector.

Figure 22: New standard actions being set up

Now all that is left is to modify the registration routine in the design-time package to refer to the data module class. Listing 11 shows the final version. One final compile of the design-time package and the job is done. A new fully-fledged standard action is available for use.

Listing 11: Registering the actions